Отдыхающие на берегу Каспийского моря наблюдают за парадом в честь Дня Военно-морского флота Российской Федерации в Каспийске, Россия. МАКСИМ КОНСТАНТИНОВ/SOPA IMAGES/LIGHTROCKET ЧЕРЕЗ GETTY IMAGES

foreignpolicy: While everyone is watching the latest drama unfold in the Black Sea, mysterious shipping journeys are taking place in the Caspian Sea. The massive lake—the world’s largest—is bordered by Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Russia, and Iran. And these days, the ocean-like sea is the scene of enormous volumes of hush-hush shipping involving primarily Russian and Iranian vessels.

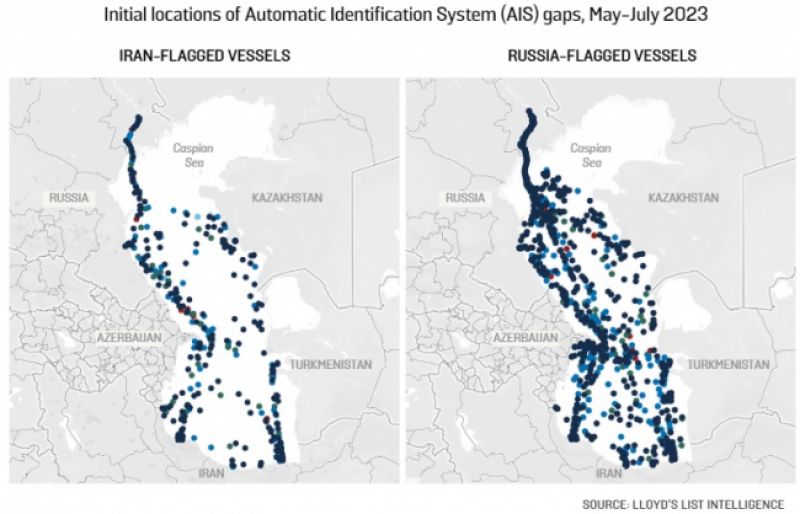

The past three months have each seen more than 600 AIS gaps by Russian-flagged vessels alone, up from just over 100 per month during the same period last year. (AIS is the automatic identification system, which virtually all commercial vessels are obliged to use; AIS gaps are the periods of time when a vessel’s system stops transmitting.) Russian and Iranian vessels traveling between the two countries are also conducting dark port calls—calling at ports with their AIS switched off—and some are even spoofing their location. Russia is entering the shadow economy.

On a recent day, 12 vessels traveling between Russia and Iran in the Caspian Sea were conducting dark port calls. (All were owned by Russian or Iranian entities, flying under Russian or Iranian flag, or both.)

The vessels clearly wanted the outside world to know as little as possible about their presence in those ports—and there’s no global maritime police force that makes sure vessels obey rules and regulations. To be sure, over the years, various ships that were up to no good have turned off their AIS—but when it happens at large scale, involving one of the world’s most powerful countries, it undermines the maritime rules that make global shipping possible.

Indeed, on the same randomly selected day when 12 vessels were making dark port calls, 12 others were conducting ship-to-ship transfers, a maneuver that is perfectly innocuous when it involves a large vessel and a smaller one that can call on smaller ports but is also common among ships trying to obfuscate their journeys.

And that’s just one part of the mystery that shrouds shipping on the Caspian Sea these days. In May, 138 Russian-flagged ships sailing on the Caspian produced 657 gaps in their AIS. In June, there were 625 such gaps involving 160 vessels, and in July there were at least 630 involving 157 vessels, according to data provided by Lloyd’s List Intelligence. That’s four times as many AIS gaps as during May, June, and July last year, when Russia-flagged ships on the Caspian Sea went dark 159, 135, and 138 times, respectively.

In May this year, 48 Iranian-flagged vessels had 199 AIS gaps; in June, 48 Iranian vessels had 218 gaps, and in July 47 vessels had 192 gaps. That’s a few more vessels per month than during the same time last year—and about twice as many AIS gaps. A significant number of the AIS-gap vessels were traveling between Russian and Iranian ports.

By comparison, Azerbaijani, Kazakh, and Turkmen ships traveling in the Caspian Sea had very few AIS gaps. They seem to be following the rules—for now. But if they decided they wanted to obscure their activities, it would be hard to stop them.

Indeed, the Russian and Iranian AIS gaps are not just the accidental kind caused by technical problems or the weather: Between 149 and 169 of them lasted four to seven days, and 50 to 92 lasted between eight and 14 days.

“In its rhetoric Russia has been pushing this route, and to some extent the Russians know they’re being watched,” said Bridget Diakun, the Lloyd’s List data analyst who conducted the analysis for Foreign Policy. “The Caspian Sea is really convenient for trade with Iran, and the Russians can bring ships there from the Sea of Azov. It seems they’re trying to hide elements of their activity, whatever that activity may be. Using AIS alone, we can’t see what exactly they’re doing, but the Caspian Sea is busier than it used to be.”

Indeed, the AIS gaps are not the only constant feature involving Russian and Iranian ships in the Caspian Sea these days. Between May to July, my research assistant, Katherine Camberg, identified regular dark port calls and ship-to-ship transfers involving Russian or Iranian vessels—often in the double digits. Things in the Caspian Sea “are just very weird right now,” Diakun concluded.

Then there’s spoofing, the practice of setting the AIS to broadcast a false position. On the same randomly selected day that saw 12 Russian and Iranian vessels conducting dark port calls and 12 others conducting ship-to-ship transfers, four Russian and Iranian vessels were spoofing their location to make it look as if they were stationary in a port off the Caspian Sea when they were, in fact, sailing some distance away in the Caspian.

Even though ships traversing the Caspian Sea between Russia and Iran don’t have to worry about inconvenient inspections in Russian or Iranian ports, they clearly think it advisable to travel surreptitiously. That may be because their business is growing. Before its invasion of Ukraine, Russia didn’t have much need for trade with Iran. In 2020, it exported a little more than $1.4 billion worth of goods to Iran and imported goods for nearly $800 million. (No, the figure was not a result of COVID-19: In the three years before that, trade between the two countries was even lower.) Then, in 2021, it leaped to Russian exports of more than $3 billion and imports of nearly $1 billion.

Leave a review