Ilgar Akbarov’s Martyrs

Events in history are not merely dates or fragments of historical memory; they leave deep marks on cultural memory as well. Artists, in particular, transfer these events into their works, shaped by their personal perceptions and interpretations. January 20 is one such event that has found its place in cultural memory. Although this topic is relatively less explored in contemporary art, it has never lost its relevance. How should this historical memory be represented? How does it manifest in art?

Independent curator and Honored Artist of Azerbaijan, Sabina Shikhlinskaya, who personally witnessed this event, has created works on this theme. In 2020, as an artist and curator, she organized an exhibition titled Discover Your Island at the Yarat Contemporary Art Center, covering the years 1988-1996. This exhibition offered a fresh perspective on art addressing this theme.

"I Have Never Left My Country"

Sabina Shikhlinskaya shared the nuances that motivated her to create works on this topic. She explained that having been born and raised in Baku, she witnessed all the significant historical events that unfolded over the years and felt herself a victim of these events.

"The January 20 tragedy is one of the most horrific events. I was in Baku at the time. My husband, father, brother, and family members took to the streets. We saw how people were killed and how innocent lives were lost."

The artist noted that people were holding peaceful demonstrations, trying to prevent violence, but tanks were used against them. At that time, these tanks belonged to the Soviet Union. People could never have imagined that tanks would be used to kill them.

All of This Deeply Influenced My Art and Creativity

"True artists reflect the reality of events in their works. Later, much of our land was occupied. Over one million refugees from Karabakh and Armenia came to Azerbaijan in dire conditions. They arrived in Baku and surrounding regions, homeless, with shattered lives and lost family members. Everything was utterly devastating."

Sabina Shikhlinskaya recalls that during the events of January 20, tanks began moving through the Yasamal area, where she lived, and the first victims were killed in that very area. People could see the tanks from the balconies of their homes.

"The next day, when we stepped outside and looked at the streets, we were met with bloodstains, destroyed cars, and people crying. It was a catastrophe that changed our lives."

She notes that the January 20 tragedy, the events of January 24, the occupation of Karabakh, and the arrival of refugees marked the beginning of one of the most challenging periods of the 1990s. According to her, many people left the country and moved elsewhere. However, those who stayed—artists, poets, and others in the arts—lived through this pain with the citizens and reflected it in their works.

A Period of Pain in Art

Sabina Shikhlinskaya explains that from 1988 to 1996, a series of negative events unfolded consecutively in Azerbaijan's history. When she saw works from that period in art studios, she realized it was a unique time.

The exhibition featured works created by her and other artists not for commercial purposes but to express the pain they experienced. It was not an exhibition of tragedy but of powerful and impactful works. Artists portrayed the events of that period exactly as they were. Moreover, photographs taken by photographers serve as documentary evidence of that era. These documents stand as genuine proof against the lies told by our enemies.

"This exhibition was a document that conveyed what happened to us to the world. The situation in other post-Soviet republics was different. After gaining independence, they began cooperating with the West. But in our case, gaining independence came alongside a period of immense destruction and hardship."

Artists’ Attempt to Create an “Island” for Their Pain

Sabina Shikhlinskaya explains that during that time, artists did not limit themselves to merely depicting tragedies. They also tried to create an “island” for themselves. The name of her exhibition, Discover Your Island, was not chosen randomly. It was inspired by a poem titled Create an Island for Yourself, written by a friend who tragically lost his life at a young age.

“The pain of those years was reflected in the works of both young and older generations of artists. For example, Rasim Babayev’s works, including his depictions of refugee women and children, are prime examples. The lost lands of that period, collective traumas, and the lack of proper international response profoundly influenced all these pieces.”

Shikhlinskaya adds that during those years, artists strove to be with the people, and this effort is vividly evident in their works.

Evolving Perspectives Over Time

Art historian Ulkar Aliyeva shared her thoughts on the works and approaches created from that period to the present day. She notes that among the various artistic approaches, elements of realism and symbolism are most commonly observed. While such historical themes are not addressed as intensively in contemporary times as they were before, some modern artists still revisit them, and we occasionally witness these themes explored from new perspectives.

According to Aliyeva, January 20 is not just an event for artists—it can also serve as a metaphor for exploring fundamental questions of existence:

What does pain look like? In what colors does injustice speak? And how can hope rise from a canvas?

Each line, color, and composition in a painting is part of an invisible dialogue—a dialogue between the people and history.

An art historian highlights works by prominent Azerbaijani artists who have addressed this theme at different times. These include People’s Artists Mikayil Abdullayev’s Baku Tragedy, Boyukagha Mirzazade’s January 19, 1990, Jhangir Rustamov’s Dedicated to the Martyrs, Kamil Najafzadeh’s Cry of Azerbaijan, Mother of a Martyr, and Waiting, Aga Mehdiyev’s Bloody Night; Honored Art Figures Hafiz Mammadov’s Martyrs and Black Holiday and Ayub Mammadov’s January Events; People’s Artist Elmira Shahtakhtinskaya’s poster Power Politics is the Disgrace of the 20th Century; and works by Honored Artists Adil Rustamov’s Cry and Arif Alasgarov’s graphic series The Tragedy of the Century, among others.

Mikayil Abdullayev’s Baku Tragedy

In Mikayil Abdullayev’s Soviet-era works, particularly his triptych In the Fields of Azerbaijan, we observe depictions of wartime backgrounds and the lives of post-war individuals. His painting Baku Tragedy portrays the cityscape following the January 20 tragedy, including the massive funeral processions for martyrs. The artist’s choice of an overhead perspective accentuates the emotional power of this mournful scene.

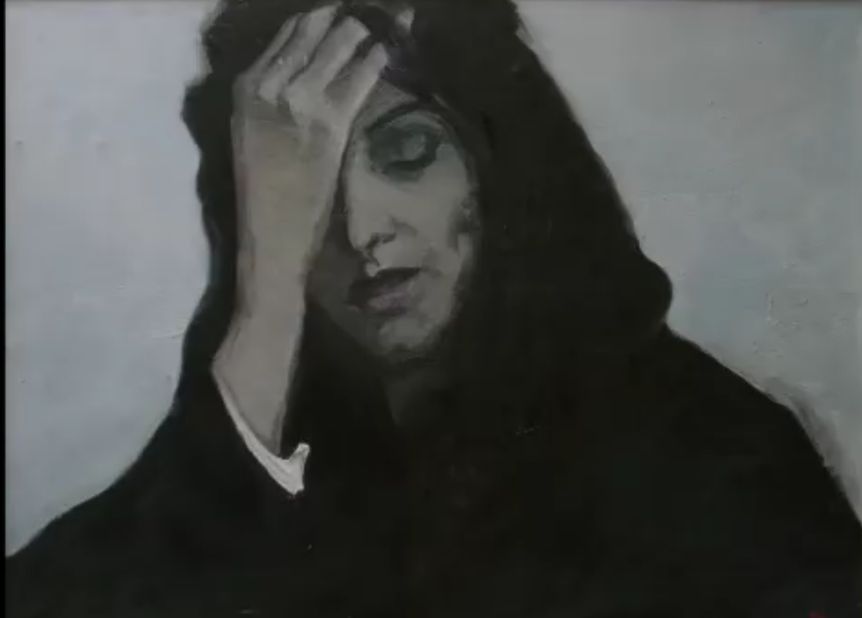

Ilgar Akbarov’s Martyrs

Art historian Ilgar Akbarov also discusses Martyrs, which offers a unique perspective on the funeral processions of January 20 martyrs being carried on shoulders to their final resting places. He notes that the use of color in the painting plays a vital role in heightening the dramatic intensity of the subject.

Kamil Najafzadeh’s Waiting and Mother of a Martyr

Kamil Najafzadeh, in works such as Waiting and Mother of a Martyr, creates a universalized image of women who have lost loved ones in such tragedies, capturing the “female” face of war through singular portraiture.

Shamo Abbasov's An Uneasy Evening

Shamo Abbasov’s An Uneasy Evening captures the aftermath of the January 20 events from a domestic perspective, portraying a small family—a man and a woman—grappling with the anxiety and unease brought about by the tragedy.

Elmas Huseynov's Song of Baku’s Dark Days

In Song of Baku’s Dark Days, Elmas Huseynov takes a slightly different approach by incorporating a traditional musical motif in the background—a trio playing mugham—to evoke the poignant melody of the tragedy.

Artists such as Arif Huseynov, Arif Alasgarov, and Telman Abbasov have also created graphic works dedicated to the events of January 20, bringing this historical moment to life through striking visual compositions.

January 20 Through the Eyes of International Artists

Art historian Ulker Aliyeva emphasizes the contributions of internationally renowned photojournalist Reza Deghati, of Iranian origin, who is one of the most prominent figures documenting the events surrounding the collapse of the Soviet Union. Alongside his coverage of the Karabakh conflict, Deghati brought the January 20 tragedy to global attention through his lens.

Despite severe restrictions, including a ban on foreign journalists entering Baku, the city being surrounded by tanks, and an information blockade, Deghati managed to travel from Paris to Baku through difficult routes.

“Risking his life, he captured scenes in hospitals and morgues, documenting the pain and reality of the tragedy, and brought it to the attention of the international community. His courageous work significantly contributed to global awareness of the January 20 events.”

Repeated Imagery and the Need for New Approaches

Ulker Aliyeva notes that artists with distinctive styles can approach any topic through their unique artistic lens. This might manifest in generalized imagery, choice of colors, or preferred styles such as realism, abstractionism, or avant-garde.

However, when it comes to works dedicated to January 20 and similar historical tragedies, recurring motifs—blood, flowers, cries, tanks, and weapons—are often reused. While these elements reflect the harsh realities of that night, seeing the same scenes repeated over the years, combined with an excessive emphasis on pathos, can diminish the emotional authenticity of the artwork.

“I believe that artists and creators should work on subjects they genuinely connect with. When addressing a specific topic, they should not hesitate to express their unique perspectives and styles,” Aliyeva suggests.

Exhibitions dedicated to tragedies like January 20 and the Khojaly genocide continue to inspire modern artists to create works on these themes.

Aliyeva highlights the example of contemporary graphic artist Leman Mammadova, who addressed the January 20 theme in her work Tragedy. In her first exploration of this subject, Mammadova’s painting features various human figures and objects intertwined in a chaotic composition.

“This approach underscores the sense of chaos and disorder, seemingly expanding the emotional scope of the tragedy. The facial expressions of the figures vividly depict emotions such as fear, sadness, and perhaps a touch of hopelessness,” Aliyeva explains.

Leman Mammadova's Tragedy

In Tragedy, Mammadova uses her unique style to present a visceral portrayal of the confusion and pain experienced during the January 20 events, making it a standout piece in contemporary explorations of historical trauma.

Contemporary artist Pərviz Kazımlı, who frequently employs collage in his work, has showcased his artistic approach to the events of January in his familiar field of art. Ülkər Əliyeva notes that the collage titled "Silent Humanity" highlights humanity's silence and powerlessness in the face of tragedies, as the name suggests. The collage draws attention with texts and images symbolizing human suffering.

For example, the phrase "Silent Humanity" expresses people's silence and inability to intervene. Pərviz uses real photos from the January 20 events in his collage, maintaining a sense of reality in the artwork. The collage includes various text fragments. The phrase "ДƏДƏ-БАБА" (Grandfather-Father) evokes the traces of the past, emphasizing that this tragedy is not limited to one period but has historical contextual significance. The use of the Cyrillic alphabet for the words also points to the Soviet authority of that time.

An art historian mentioned that the phrase "ДƏРМАН АЧЫ ОЛСА ДА…" (Even if the medicine is bitter) reflects the desperation people faced during these events, no matter how bitter it was, and it also recalls the bitter beginnings, such as the January tragedy, on the path to independence. The name and content of the collage show how silent and passive humanity can be in the face of tragedies like those on January 20.

Pərviz Kazımlı "Silent Humanity"

Ülkər Əliyeva and graphic designer and illustrator Cəmilə Əhmədova emphasized that her work "January 20 Legacy" was inspired by real photos. The image of an elderly woman represents women who lost family members, relatives, or acquaintances during the January 20 tragedy.

"The image of a mother holding a red carnation, a symbol of the tragedy, in a silent and sorrowful state seems to have accepted the pain that has existed for years. This shows how the impact of the tragedy permeates not only individuals but also families and the entire society. The winter scene visible from the window directly refers to January when the events took place."

Cəmilə Əhmədova "January 20 Legacy"

Abstract artist Könül Rəfiyeva explains a tragedy in abstract artistic language in her work titled "Wounded." The piece symbolically expresses the concept of collective trauma through both color and its textured fabric. The dominance of deep red and black colors in the artwork, along with the bullet wound and the trail of blood in the upper right part, symbolizes both physical and emotional wounds. This blood represents not only the indelible marks in the memory of an individual but of an entire nation. The continuation of the blood flow suggests that this trauma has not remained in the past; it still follows us today and we are still trying to heal our wounds.

The raised textures on the right side of the piece might represent wounds, possibly those that are healing but still hold painful memories. These textures seem like a material transformation of both raised and deep-seated pains. In the upper left, lighted windows are reflected. The use of yellow implies that everyone was awake that night, but the darkness – the black color – smothers that light. This visualizes the traumatic experience of both individual lives and an entire collective. The images reflected below, like gray and modern buildings, represent the era of independence, but the “trails of blood flow” above them show the difficulty of escaping the influence of the past. Könül explains the inability of the colors to be fully vibrant in the process of creating the artwork due to the pervasive influence of the underlying red color. "Wounded" profoundly communicates how a trauma is etched into collective memory and how it leaves a lasting impact across generations. The wounds do not heal, but life continues – this is reflected both in the visual language and the inner essence of the work in abstract terms.

Könül Rəfiyeva "Wounded"

Ülkər Əliyeva says that Sahib Yaqubov's "Contrasts" is a powerful metaphor that symbolizes the transience of human life and the difficult days of our history. According to her, the burning candles in the work reflect the lives lost and dreams unfulfilled during the events of January 20, the Khojaly Genocide, and March 31. The completely burnt-out candles represent the ended lives of martyrs, the melted candles symbolize those living with trauma, and the unlit candles indicate a destroyed future and shattered hopes. The concept of "contrast" in the work expresses the tension between light and dark, hope and despair, while the use of marble and bronze materials highlights the harshness and unforgettable nature of that night.

Sahib Yaqubov "Contrasts"

"The works, by showcasing the consequences of violence through art, highlight the traumas brought by war and disasters. However, the importance of peace should not be forgotten. Peace is not only an ideal but also a collective healing process. Learning from the pains of the past, we must work for peace and reconciliation, and maintaining a culture of peace should be accepted as a collective responsibility."

Finally, art historian Sahib Yaqubov touches on his "QR Code" series, including "QR Code: Peace" and "QR Code: Freedom," which feature a white dove at the center representing the ideals of peace and freedom.

"The surrounding colorful and geometric QR codes symbolize the role of modern technology in human life. 'Reading' the QR codes is likened to the process of achieving freedom and peace, thus the artist emphasizes the universal value of these ideals across all eras."

Sahib Yaqubov "QR Code: Peace" or "QR Code"

The tragedy of January 20 is not only a painful memory of the past but also a lesson for the future. Art, while reviving these pains, also promotes the ideals of peace and freedom. War and violence not only leave behind tragedies but also remind us of the need to stand against them and the need for peace. The lessons of January 20 become more relevant with each new work and today remind us again of the importance of peace.

Leave a review