The road from Aghdam to Shusha. google map

The road in Karabakh is blocked. Communication between settlements is broken and civilians cannot move around as before. Russian peacekeepers escort ambulances and humanitarian aid, breaking through barriers.

No, it is not December 2022 in the yard. Behind the loopholes of the IFV, November 1989.

The Lachin corridor is open. Armenians move freely from Karabakh to Armenia and back. The Azerbaijanis stare blankly at the Armenian vehicles climbing and descending the serpentines.

The situation is quite different just tens of kilometers from here. From Agdam to get to Shusha, which are separated by 39 km, without the escort of the Soviet military (read Russian) was not possible. The Armenians block the road in three places: between Agdam and Askeran, Askeran and Khojaly, between Khojaly and Shusha.

I am standing on the outskirts of Agdam and peering into the dark, almost black wooded mountains of Karabakh. It is no coincidence that this region was called Karabakh (translated from Turkic - Black Garden). We were to advance to Khojaly together with the military of the Agdam commandant's office of the Internal Troops of the USSR, which was conducting a peacekeeping mission. I, the correspondent of the military-legal department of the Azerbaijani branch of TASS - Azerinform, and our photojournalist Farid Khairulin, were sent once again to describe the situation from the scene.

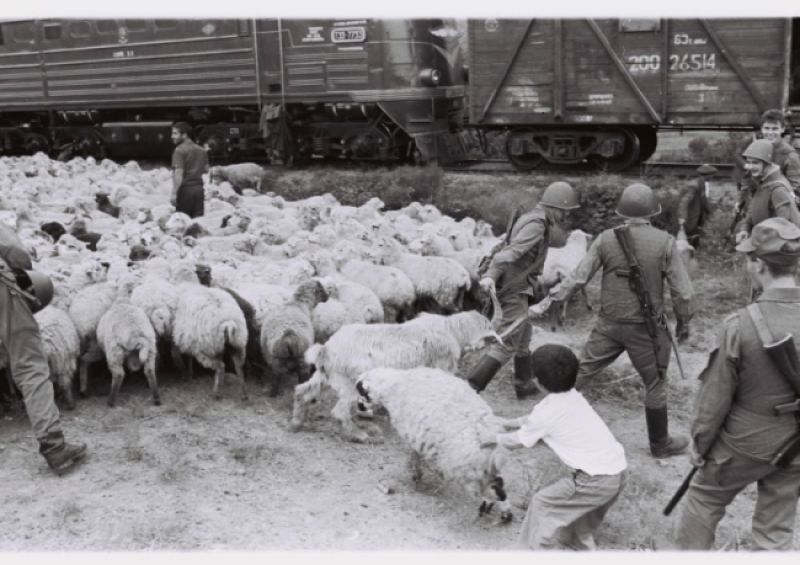

A large herd of sheep is concentrated in Khojaly, which the Agdam shepherds brought here in a roundabout way from the Kalbajar mountain pastures. Further movement was impossible. The Armenians blocked the road. The herd belonged to the collective farm. Lenin in the Agdam region and it was necessary to return the sheep here. The commandant's office discussed the situation. The plan was as follows: we were advancing to Khojaly on two infantry fighting vehicles. There will also be a freight train. We load the sheep into the wagons and return, accompanied by peacekeepers.

From the deputy commandant of a stocky, strong officer, Major Vasily Aksenov (name changed), I learn that Robert Kocharyan is in the hospital in Askeran. It was reported that for security reasons, the head of the separatists chose this place. I asked to arrange a meeting with him for an interview. We drive to the hospital. Major goes to the hospital. From the second floor, the medical staff examines us with curiosity, and a man peer out behind them. Looks in our direction and disappears. Aksyonov returns: "He said he wouldn't talk to you."

We are moving on. And here we are in Khojaly. The day is cold, people are emaciated, tired. Together with Khairulin, they started a conversation with a group of local men. They are looking at us inquisitively with hunting rifles at the ready.

“How are you?” I ask. "It's difficult, but we're not going to retreat," said one of the Khojaly residents. But then it got worse: "The Russians pander to the Armenians, who bribe them. Every day they bring them alcohol, food, women. Therefore, they are on their side. They also steal our sheep."

Khairulin edifyingly tried to explain to them what countermeasures should be taken in this case: "You do the same." The people of Khojaly tensed up. One pulled the gun from his shoulder. The situation was getting out of control. “Just a minute, a minute,” I say. “He meant food and alcohol.” He explained that Khairulin is a Tatar-balasy (is a Tatar), he does not know the intricacies of Azerbaijani. The hand of the Khojaly man on the gun belt slid down. Got sick. “Where is all this happening?” I ask.

“Over there,” indicates that the younger ones are on the trailer of peacekeepers, which is a hundred meters away. We head to the trailer-post. With us is the same Aksyonov from the Agdam commandant's office. The door to the trailer is locked. We knock. After a while, the door opens, and a Russian police officer falls out. The face is angry, swollen from alcohol. Seeing the representative of the commandant's office, he pulled himself up a little, fastening his buttons.

“Here they are pandering to the Armenians,” said a young resident of Khojaly, reinforcing the accusation with the fact of a ram stolen the day before by the inhabitants of the post. "Can you prove it?" I asked.

The Khojaly resident, without further ado, crouching, began to move, scattering foliage. At 10 and in meters from the trailer, he threw up a brown sheep skin sprinkled with earth and leaves. Aksyonov blushed. Then the officers sorted it out without us.

A couple of hours later the train arrived. The soldiers helped the shepherds load the sheep and we returned to Agdam according to the planned scheme - the IFVs moved on both sides of the train, making it clear that he was under cover.

This story had a funny sequel. Upon arrival in Baku, we are called by the director of Azerinform Azad Sharifov: “What did you write, what occupiers, what sheep?”

The newspaper Youth of Estonia published a photograph taken by Khairulin showing soldiers herding sheep into wooden boxcars. The photo was accompanied by the following comment: "Soviet invaders are taking sheep out of Karabakh."

Karabakh. Khojaly. 1989. Photo: Farid Khairulin

“The claims are not against us, but against TASS, which distributed the material,” I replied to Azad.

The next day, November 6, a convoy with humanitarian cargo, accompanied by peacekeepers, advanced to the blockaded Shusha. When passing by Khankendi (Stepanakert), the convoy stopped and our ZIL-131 froze after the rest of the cars. Through the canvas window above the driver's cab, I watch the peacekeeping unit moving towards the large group of Armenian men blocking the road.

Karabakh. Unblocking the road to Shusha. 1989. Photo: Farid Khairullin

Khairulin with a camera at the ready runs forward. I was strictly asked not to get out of the car. But as soon as the military left, I jumped out of the car and headed towards a group of Armenians - people shouting aggressively in Armenian, reinforcing the verbal expression with the swing of their fists. I stood two or three meters away from them, looking at the action. They did not seem to notice me. I was dressed in luminous jacket and light corduroy trousers, which distinguished me from the locals. Yes, and they could not think that an Azerbaijani could stand in front of them so brazenly at such a dramatic moment for them.

Shots were heard ahead. They fired into the air. The blockers were laid on the asphalt. A little later, the road opened. Humanitarian aid was unloaded in Shusha. In the evening we moved back. The column moved as fast as the local mountain roads allowed. We had to slip through the same section near Khankendi as quickly as possible. The Armenians used to shoot stones at the cars from the hill above the road. From above, several large stones hit the ZIL tarpaulin. But it passed.

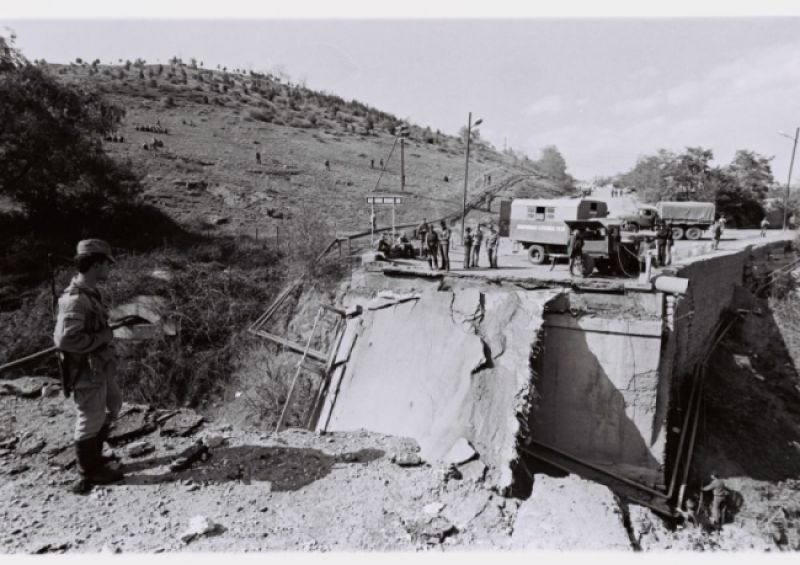

On the night of November 6-7, information was received that the Armenians had blown up the Aga Korpusyu (Master's Bridge) bridge between Khankendi and Shusha. Shusha was completely blocked.

In the morning, two armored personnel carriers arrived at the destroyed bridge. Farid went to shoot the blown-up bridge, and once again I was asked not to leave the shelter. Our regional correspondent Chingiz Ismailov, who was nearby, also advised not to leave the APC. Chingiz, a former employee of the regional council of Nagorno-Karabakh, was forced to leave Khankendi, even though he was a half-breed - an Azerbaijani father and an Armenian mother. I looked at him without saying anything and went to inspect the bridge. It was torn in the middle, concrete slabs hanging down. Farid filmed. The military and local Armenian officials were talking about something. Chingiz sat on an armored personnel carrier sadly peering into what was happening.

Karabakh. Aga korpyu bridge. 1989. Photo: Farid Khairulin

I climbed onto the combat vehicle and sat down. A “Zhiguli” car was passing by with the same Armenian officials that were at the bridge. The two on the right, through the open windows, silently nodded to Chingiz, greeting in this way. This was the only positive moment from our entire blockade epic that inspired some optimism.

Leave a review