Phantom F4 2020 Turkey

thedrive.com/the-war-zone: Turkish McDonnell Douglas F-4E Phantom IIs have been operating for nearly five decades, an exceptional lifespan for some of the last frontline third-generation fighters. They once ruled the skies, but today face a growing number of threats and have been outclassed by more advanced adversary fighters. So, how do these historically famous aircraft fit into Turkey’s modern fight? We got a good idea of just that at Turkey’s large Anatolian Eagle (AE) exercise earlier this month.

The AE 2023 exercise involves training alongside partner nations to reduce the loss of inexperienced fighter pilots and their aircraft in potential real-world combat missions, as well as keeping up fighter crews' and GCI (Ground Control Intercept) radar operators' readiness. It provides them with an opportunity to increase their interoperability and simulate working in a coalition air combat environment.

Since its establishment in 2001, 43 AEs have been performed at the training center located at the 3rd Main Jet Base at Konya. A total of 15 NATO countries have participated in them, including France, Italy, Germany, the United States, and Spain. The unique feature of the event is the size of the airspace and tactical ranges — 120 by 216 nautical miles wide — which allows for more than 60 aircraft to employ their tactics away from any surrounding air traffic for AE missions.

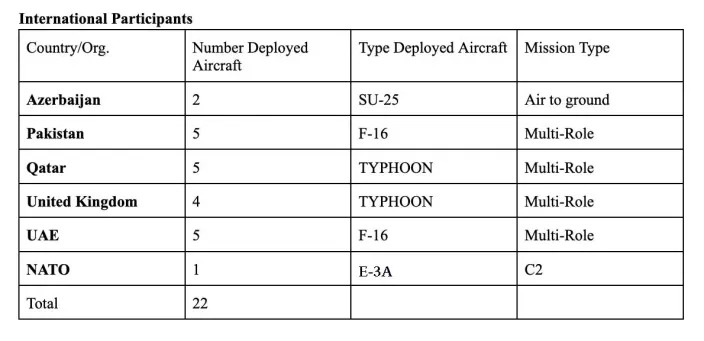

The 2023 edition included five international participants alongside Turkish units — Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom — which all contributed their own assets. Additionally, NATO as an organization, also provided one of its E-3 AWACS aircraft for the event. Observers on the ground comprised personnel from Morocco, Libya, and Georgia.

A United Arab Emirates Air Force F-16E Desert Falcon. Author's image

An inert AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missile under the wing of the F-16E. Author's image

Author's image

A Pakistan Air Force F-16D. Author's image

Author's image

A Qatari Emiri Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon. Author's image

A line-up of Turkish Air Force F-16s. Author's image

A Turkish Air Force F-16 demonstration jet. Author's image

Author's image

Elements of AE training are divided into three categories: white headquarters (command and control), red force (training aids), and blue force (training recipients). The role of the white HQ is to develop fighting scenarios, determine the level of training, and assess the crew’s obtained results. The red force is composed of ‘Hammers’ and ‘Hançer,’ which are respectively air defense personnel and aggressor pilots, in charge of performing simulated attacks in order to detect vulnerabilities as well as punish mistakes made by the blue force.

According to Turkish pilots, ‘punishment’ is usually in the form of a simulated lock and kill, which is checked post-flight to confirm. In contrast, blue units conduct joint air missions such as Composite Air Operations (COMAO) and attacks on the red territory defended by ground-based air defense systems.

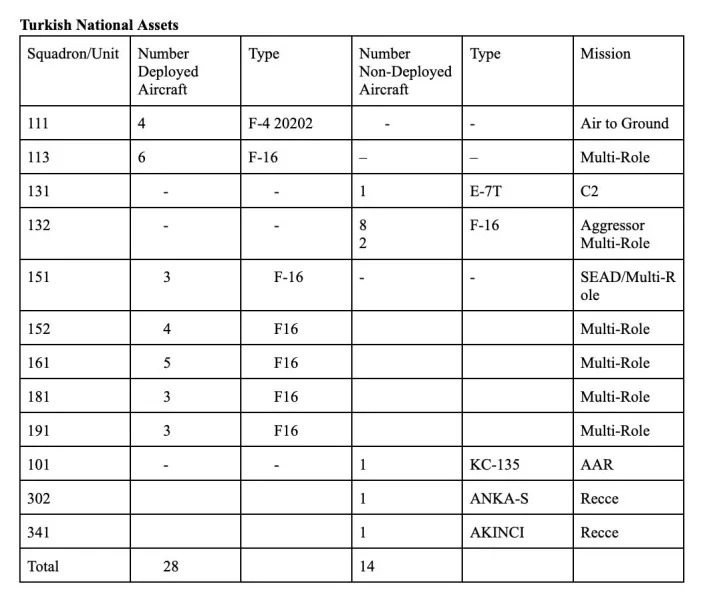

Scenarios change every year based on participants' requirements in terms of different threats. In this edition, two countries were depicted between red and blue lands, divided by a fictional pipeline that was under attack by a national terrorist group. Although imaginary, the scenario does reflect real-world elements, with the terrorism threat faced by Turkey and participating nations having increased in recent years.

Presentation of the 2023 leading intelligence scenario at Konya Air Base. Author's image

Participants are also offered the opportunity to fly missions during non-AE sorties in accordance with their training needs, including tactical intercept, dissimilar air combat training (DACT), and electronic warfare duels. Overall, the objectives of the exercise called for the blue fighters to carry out 240 sorties and have 110 targets planned for them.

According to statements and videos released by the Azeri MoD, some of the daily tasks practiced included successfully silencing the conventional enemy’s air defense means.

“After gaining air superiority, our planes [Su-25s], together with various fighter planes [confirmed to have been F-16s, F-4Es, and Eurofighters], entered the airspace of the conventional enemy and carried out complex combat maneuvers at both medium and high altitudes to destroy the enemy's stationary ground targets camouflaged in mountainous areas.”

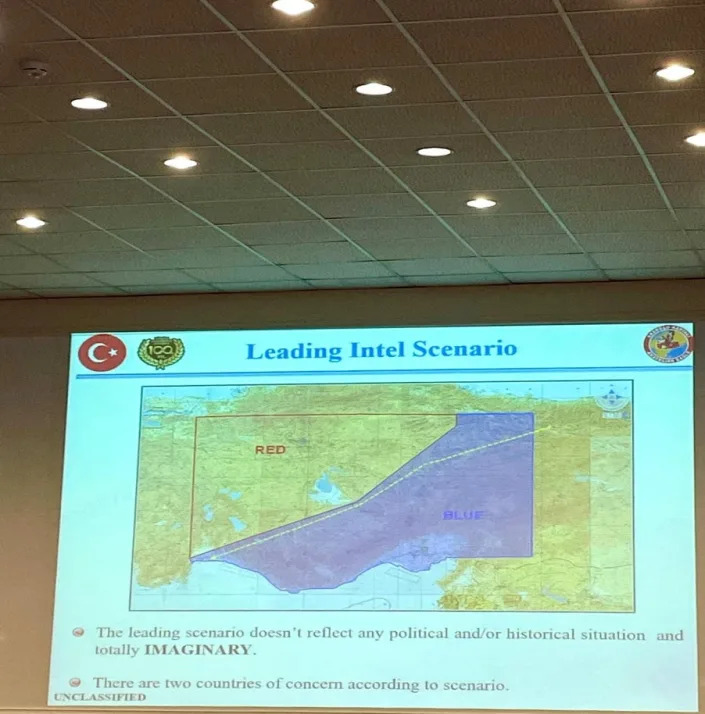

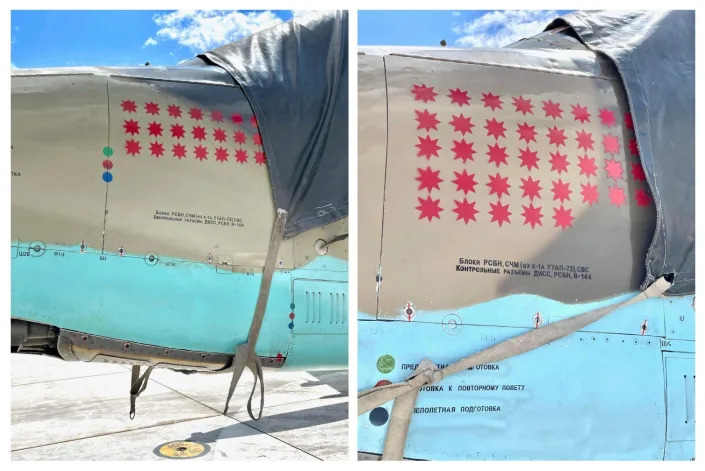

For a second year, Azerbaijan’s battle-hardened Su-25s took part in the training, these jets each wearing more than a dozen airstrike markings, representing Armenian targets hit during the 2020 conflict. They also displayed for the first time the aircraft’s latest standoff capability, with Turkish glide bombs, offering a hard-hitting strike option. The Su-25s also carried Israeli Elta EL/L-8222 self-protection pods, similar to those on Turkey’s F-4Es.

An Azeri Air Force Su-25 fitted with an EL/L-8222 pod. Author's image

Author's image

Author's image

Author's image

Two Azeri Su-25s displaying red star markings indicating Armenian assets successfully attacked. Author's image

That brings us to Turkey’s venerable Phantoms, which are in the twilight of their careers but were still very active at AE 2023.

The Turkish Air Force embarked on a considerable modernization journey for some of its Phantoms in the late 1990s, signing a $632-million deal with Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI). That agreement would see 54 of the roughly 200 F-4Es it had in its inventory upgraded to Terminator 2020 configuration. The project was dubbed F-4E-2020, in light of its objective to keep the aircraft flying at least until that year. Out of the 54, about half were considerably modified by IAI in Israel with new avionics systems, originally destined for the country’s own ‘Kurnass’ Phantom program before it was canceled. The remaining airframes were upgraded in Turkey via kits provided by Israel.

The new Turkish Terminators were fitted with:

Elbit’s ELOP 976 wide-angle head-up display (HUD) and hands on throttle and stick (HOTAS) flight controls;

Higher-performance Elta EL/M-2032 multimode airborne fire-control radar (initially developed for IAI’s Lavi indigenous fighter program);

Elta EL/L-8222 electronic countermeasures pod;

Dual MIL-STD-553B databus avionics package;

AN/ALQ-178 passive self-protection suite;

New UHF/VHF radio antennas and onboard multifunction displays;

New GPS/INS precision targeting navigation equipment.

Additionally, the F-4Es were also armed with enhanced air-to-ground capabilities, including the Israeli AGM-142 Popeye standoff missile, AGM-65A/B Maverick air-to-ground missiles, and GBU-10/12 Paveway laser-guided bombs.

Two Turkish F-4E-2020s at Konya Air Base for Anatolian Eagle 2023. Author's image

The number of active F-4E-2020s varies according to different accounts, but most analysts have placed the number of operational airframes at between 30 and 40. Today, only one Turkish F-4 squadron remains — 111 Filo ‘Panterler’ based out of the Eskisehir Air Base. Four of the iconic fighters from the unit were deployed to Konya for this edition of AE.

Author's image

Author's image

Author's image

Author's image

Speaking about the relevance of these aircraft in training operations, the deputy chief of the Turkish Air Force Public Affairs Office, Maj. Akbay, told The War Zone, “We still actively use the F4-E-2020, as its avionics improved thoroughly in the air-to-ground role. Since it is also equipped with self-protection ECM pods, we primarily rely on it as an air-to-air escort and protection in the air theater. In both the AE exercise and in real-life operations, we coordinate and fly with both national and international air-to-air assets, such as F-16s and UAVs.”

He declined to answer whether the Turkish Air Force is training new pilots to operate the Phantom. Greece, another F-4 operator, disclosed in a 2021 interview that the Hellenic Air Force was still training co-pilots to fly the aircraft and that it took an average of four years for them to progress to a front-seat role.

Douglas Barrie, a senior research fellow for military aerospace at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, says: “Upgraded Turkish F-4s retain combat utility in that they would be able to be operated in permissive airspace — where there was little anti-air threat or to operate outside of highly contested airspace if the aircraft were fitted with standoff weapons in the air-to-surface tasks.” He adds that there also arguably remains value in having two aircrews for some roles at least.

Yet, as echoed by the Turkish official, the fighters can be reliable assets for EW escorts, especially thanks to their EL/L-8222 pods. These battle-proven pods remain highly effective 20 years after their introduction, enabling enhanced survivability in the face of adversary radar systems including ones found on modern fighters.

Turkey's remaining F-4s can further serve as standoff shooters for TV-guided Popeye missiles that carry a nearly 800-pound warhead and have a range of around 50 miles.

Author's image

Author's image

While we do know that the country’s F-4E-2020s will keep flying until at least 2030 — following the U.S. decision to not sell the F-35 to Turkey over its purchase of Russian S-400 air defense systems — the Turkish representative said there is no official date known for when they will be retired. What is likely to play a decisive factor in this is when its latest TF-X indigenous stealth fighter — now named Kaan — becomes operational and/or the country’s high-performance Kizilelma drone.

Turkey's TF-X prototype undergoing taxi tests. TAI

Last December, Turkish media reported that TF-X would take its first flight in 2024 and that the first unit could be delivered as early as 2028. There is, however, as some analysts have pointed out, a major difference between flying a fifth-generation prototype aircraft and actually mass-producing it. Off the record, several sources have expressed a certain level of doubt regarding the intense timeline outlined for the TF-X program.

Barrie concurs, stating that, “Any goal of introducing the Kaan into service by the end of the decade remains ambitious, in part given that delays and technical challenges are part and parcel of combat aircraft development.”

The timeline surrounding the Kizilelma unmanned combat air vehicle is also ambitious, but the system has already taken its first flight.

Until then, the Phantom remains a combat-ready tool that nearly 50 years after its introduction still has a relevant place in Turkey’s aerial order of battle. It is clear that these nearly antique fighters are not hangar queens just yet, and are still actively involved in operations that benefit from their unique attributes.

Regardless, getting to see F-4s still earning their keep in 2023 is something to behold.

True to their name, it likely won’t be all that much longer until they disappear for good.

Leave a review