- The difficult Road to Independence

- The Trabzon conference and road to independence

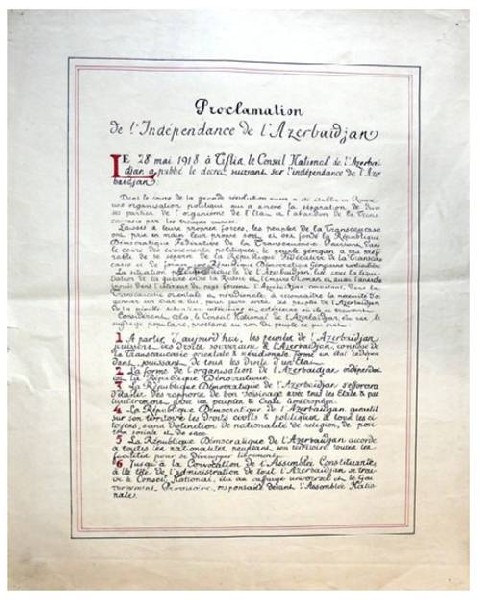

- Declaration independence of Azerbaijan

- Summer 1918: The Defeat of the Bolsheviks and the Crisis in Baku

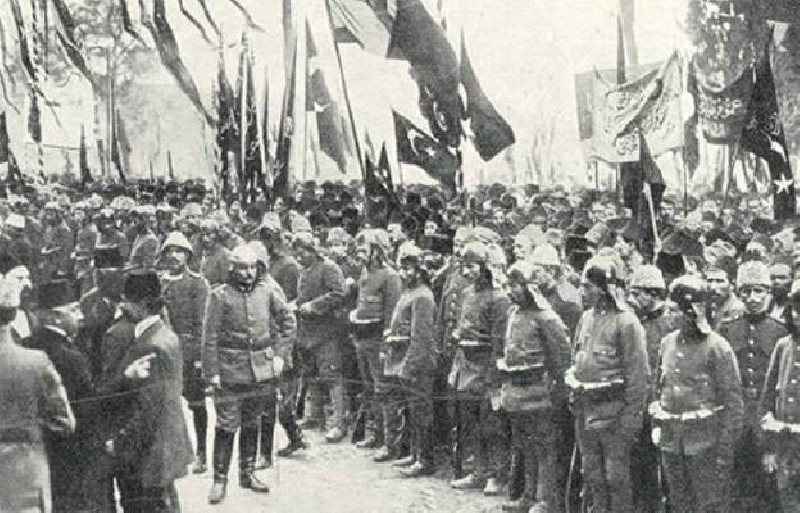

- The liberation of Baku

- The Mondros Armistice and Azerbaijan

- The opening of the Azerbaijani Parliament

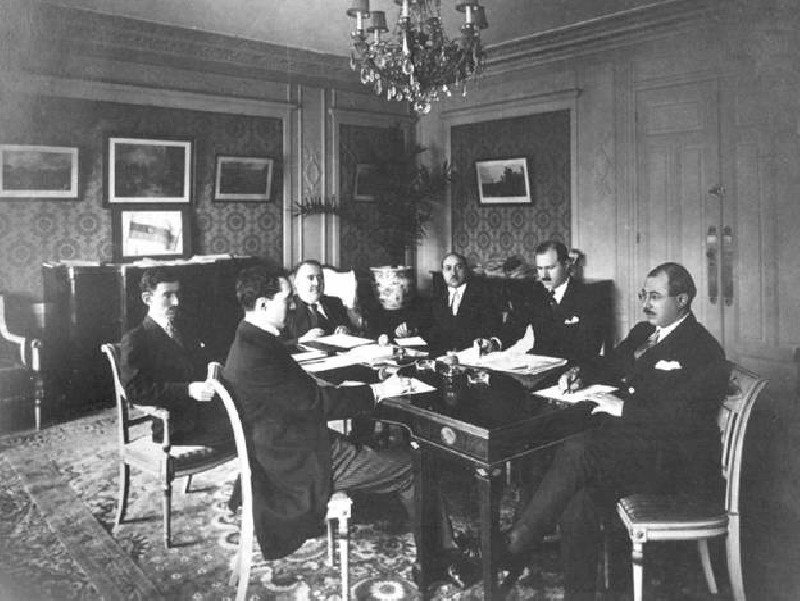

- The Creation of the Peace Delegation of Azerbaijan

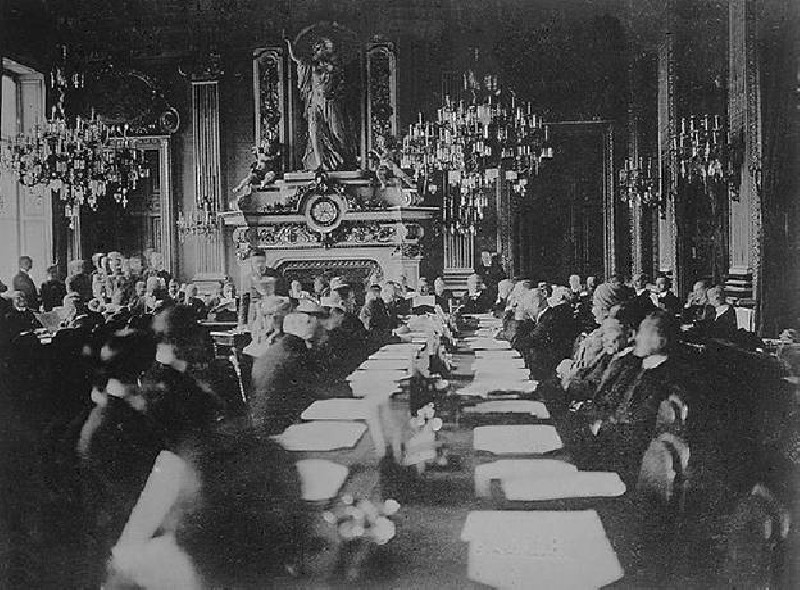

- "Russian question" at the Paris Peace Conference and Azerbaijan

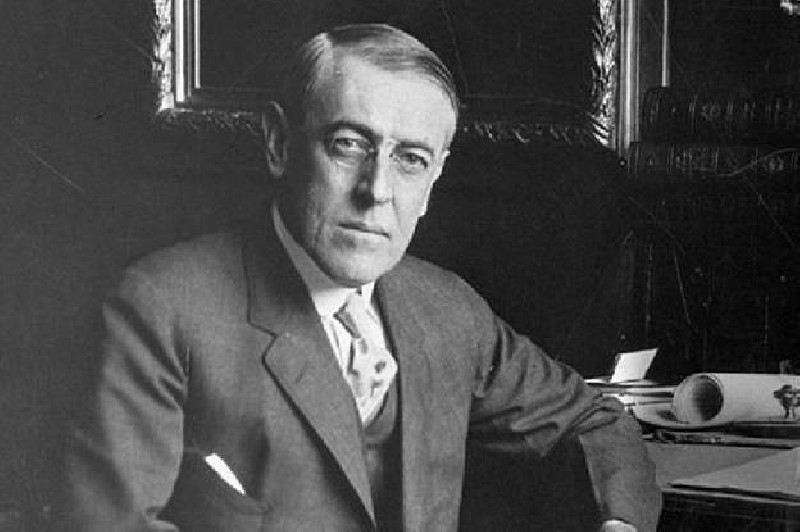

- The Meeting of Azerbaijan Delegation with President Wilson

- The First Anniversary of Independence and Danger from the North

- The defense pact between of the Azerbaijan and Georgia

- Azerbaijan Republic confronts the claims of "Great Armenia"

- Mandate system and Azerbaijan

- The United States interest in the Caucasus and Azerbaijan

- The spread of propaganda in Western Europe

- The strengthening of the Bolshevik danger and Azerbaijan

- Recognition of Azerbaijan`s independence

- The Allies military assistance to Azerbaijan

The difficult Road to Independence

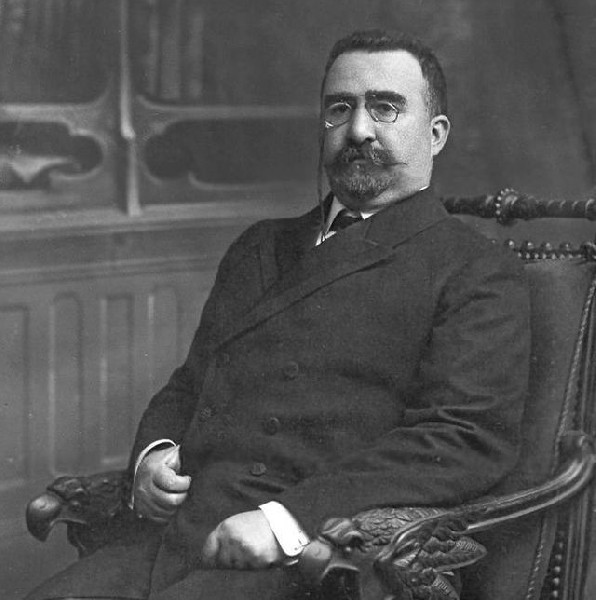

The Azerbaijan Republic, which appeared on the stage of world history in 1918, was a secular state, a logical result of the transition from Islamic populism to Turkish nationalism and a historic confirmation of the philosophy of "national awakening," including the desire to be a distinct and unified nation. Not seeing the footprints of their nation among the nations of the world and suffering from this, the leading minds of Azerbaijan seized the first opportunity presented and succeeded in establishing the first Azerbaijan republic on May 28, 1918. This significant event was a great historical achievement for the Azerbaijani nation and their hope for a change in the political map of the world-a world where diplomatic conflicts were being resolved by cannonballs exploding on battlefields and the situation was becoming tenser from day to day.

The Azerbaijan Republic survived for only twenty-three months. This is not a very long period of time, and yet the history created during those months, the steps taken in the sphere of diplomacy, and the political ramifications of important actions and policies introduced during that period changed the path of the nation. The independence announced on May 28, 1918, and the tricolored flag with crescent and star that was raised to the sky as a symbol of this independence were not only the logical result of a national struggle spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but served as an ideological guide for the future of a new country, a strategy encompassing national targets and goals.

The Azerbaijan Republic was formed at a time of intense diplomatic struggles that accompanied the end of World War I and attempts by Russia to restore the borders of its empire. This demanded from the young Azerbaijani republic great diplomatic skill and an ability to recognize turning points in world politics. Azerbaijani diplomacy managed to fulfill its duty during the two years of independence, and that duty was characterized by the combination of a love for freedom and a struggle for autonomy. Those who represented Azerbaijan in the international political arena gained acceptance in 1920 at Versailles, but postwar geopolitics prevented the Azerbaijani people from deriving the full benefit of their achievements. The Azerbaijan Republic ceased to exist in April 1920, not due to political processes or territorial conflicts within the country but due to the complicated conflicts taking place in world politics. In truth, the difficulty of integrating the new Caucasus republics, including Azerbaijan, into the international arena was related to the collapse of Russia, which was a member of the Entente, the winning bloc of countries in World War I. The victors did not anticipate the collapse of Russia, and their ruling circles were not ready to recognize the new republics that emerged from the ruins. Russia"s allies viewed Bolshevism as a temporary condition and did not lose hope that the country would restore its old borders. They therefore acted with extreme caution on all issues concerning this former world power.

***

World War I brought Russia unforeseen disaster. Along with the overthrow of the tsarist monarchy in Russia, the revolution of February 1917 was a blow to the Russian empire, spawning national liberation movements in that "prison of nations." The overthrow of the monarchy sped up the political processes taking place in the South Caucasus. One of the first steps of the Provisional Government that was formed after the revolution was the creation of a special institution to govern the South Caucasus. On March 9, the Special Transcaucasian Committee (OZAKOM) was created to govern the region. Its members were drawn from the State Duma, and it was chaired by the Russian Constitutional Democrat Vasily Kharlamov. The Committee consisted of the Social Federalist Kita Abashidze succeeded by Menshevik Akaki Chkhenkeli from Georgia, Azerbaijani Constitutional Democrat Mahammad Yusif Jafarov (who later occupied the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs in the fourth cabinet of the government of the Azerbijan Republic), and Armenian Constitutional Democrat Mikayel Papajanov.

The Special Committee was directly subordinate to the Provisional Government. As this institution was created for the management of civil issues, it did not have legislative authority. Due to its limitations, the Committee was overwhelmed by events. The growing trend of the Transcaucasian nations toward autonomy and political freedom, inspired by the February revolution, along with the legalization of the activity of numerous national parties and organizations as well as increased interest on the part of the international community, seriously complicated matters for the government of the South Caucasus.

On March 27, representatives of Muslim organizations and societies in various localities met in Baku to form the Muslim National Council with a temporary executive committee chaired by Mahammad Hasan Hajinski, who later became the first Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Azerbaijan Republic. The Musavat (Equality) party, founded in Baku in 1911 by Mahammad Emin Rasulzade, had the greatest weight in the Council, and it soon emerged as the all-Azerbaijani party. In the election to the Baku Soviet held in October 1917, the Musavat party collected nearly 40 percent of all the votes cast: 9,617 votes of some

25,000. Despite the fact that the elections were held at a time considered to be favorable for them, the Bolsheviks gathered only 3,823 votes, while the Socialist-Revolutionaries received 6,305, Mensheviks 687, and Dashnaks (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) 528. The October elections demonstrated which party was the strongest. This success was due to the fact that the Muslim masses were being attracted to political processes and to the demands of national organizations to grant Muslims full political rights.

The idea of national and territorial independence was discussed for the first time at the Congress of Caucasian Muslims held in Baku on April 15-20, 1917. The Musavat party and the Turkic Federalist party founded in Ganja (then called Elizavetpol) under the leadership of Nasib bey Usubbeyov (Yusifbeyli) and Hasan bey Aghayev after the February revolution emerged as the dominant political organizations. After long debates, the congress passed the following resolution on the national issue: "The federal democratic republic is to be recognized as the best structure for securing the interests of Muslim nations within the Russian state system."

The Baku congress stipulated the protection of national schools by the state, the opening of a university in the mother tongue of Azerbaijani citizens, the enlargement of the Special Transcaucasian Committee to include Muslims, a census of the Muslim population, and the marshaling of the military potential of the Muslim population in view of the imminent danger. An argument between Turks who were in favor of territorial autonomy and Islamists and Socialists who were in favor of national cultural autonomy lasted for 10 days after the conclusion of the congress and continued at the All-Russian Congress of Muslims held in Moscow on May 1, 1917. At the Moscow congress, Socialists justified their objection to territorial autonomy by stating that it would undo the achievements of the revolution and that within a framework of national cultural autonomy, the Russian central government would act as the guarantor of the protection of the rights of Muslims.

On May 3, Mahammad Emin Rasulzade, in his main address to the congress, explained the importance of demanding territorial autonomy and backed his words with strong arguments. To those who stressed the Islamic factor as the crucial one, he noted that many Turkic nations had already realized that "first of all, they are Turks, and then they are Muslims." Rasulzade stated that the question must be put in the following way:

"What is a nation? I am sure that such characteristics as unity of language, historical relations, and traditions create a nation. Sometimes, when Turkic Tatars are asked about their nationality, they say they are Muslims. However, this is an incorrect viewpoint. Christians do not exist in one nation; neither do Muslims. There must be a place for Turks, Persians, and Arabs in the large house of the Muslim faith." Rasulzade, who has been labeled a pan-Turkist in both Soviet and foreign literature, noted in his speech to the congress that the Turkic nations differed greatly from one another. Despite the strong opposition of the proponents of cultural-national autonomy, the idea of territorial autonomy, proposed by Rasulzade, was accepted with 446 votes in favor versus 271 against. After the victory of the idea of territorial autonomy at the Moscow Congress of Russian Muslims, the party of Turkic Federalists and the Musavat party decided to merge due to the similarity of their aims and purposes. After preparations in May-June, at the first congress held in Baku on June 20, the merger was completed, and a joint central committee was created.

Intellectuals of Azerbaijan who did not join any political party nevertheless considered it important to preserve and protect the achievements of the February revolution. During the revolt led by General Lavr Kornilov against the Provisional Government, leaflets were distributed bearing the signature of Ali Mardan bey Topchubashov and expressing the solidarity of the Muslims of the South Caucasus with the Russian revolution. Topchubashov was elected chairman of the Muslim National Council in Baku, and Fatali khan Khoyski, who was also a member, was sent on an official trip to Petrograd to participate in a discussion concerning elections to the Constituent Assembly.

When the revolution of October 1917 occurred, it raised the hopes of the nations that had been subjects of the Russian empire. These hopes for independence were for the most part nourished by the declarations made by the Bolsheviks in the early days of their coming to power. A peace decree and a Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia were to provide a guarantee that the nations of the former empire would be free to secede and create independent republics. However, quite soon it became clear that these documents were merely propaganda.

While the October events were under way in Petrograd, the Musavat party convened its first congress, which lasted for 5 days. The congress defined the tactical and strategic direction of the national territorial autonomy of Azerbaijan in view of the existing conditions. Mahammad Emin Rasulzade was elected as the chairman of the central committee of the party.

On November 11, a meeting of political organizations of the South Caucasus was held in Tiflis (today"s Tbilisi). The leader of the Georgian Mensheviks, Noe Jordania, gave a long speech in which he said that, for the last 100 years, the South Caucasus had lived shoulder-to-shoulder with Russia and considered itself "an integral part of the Russian state." Now a catastrophe had occurred. The connection with Russia was lost, and the South Caucasus was on its own. "We need to get up on our feet, either to save ourselves or be destroyed in the whirlpool of anarchy." Jordania proposed the creation of an independent local government to save the South Caucasus from disaster. It was decided that, until the governance issue was resolved by the Constituent Assembly, a South Caucasian Commissariat would be created to govern the region. On November 15, the structure of the newly formed government was announced.

Since autumn 1917, Muslims of South Caucasus started their preparations for elections to the Constituent Assembly. In Ganja congress was held here to elect candidates from the Muslim Committee and the "Musavat" Party. In debates were formed a bloc of the Muslim National Committee and "Musavat" that included Mahammad Yusif Jafarov, Ali Mardan bey Topchibashov, Mahammad Emin Rasulzade, Nasib bey Usubbeyov, Fatali khan Khoyskii, Hasan bey Aghayev, Khosrovpasha bey Sultanov, Gazi Ahmed Mamedbeyov, Mustafa bey Mahmudov, Mir Hidayat Seyidov, Aslan bey Gardashov, Shafi bey Rustambeyov et al. Aside from that, Ali Mardan bey was nominated from Syr Darya province; Mahammad Emin bey from Fergana region; Nasib bey from Amu Darya province. This shows that progressive Azerbaijanians played a leading role in the political life of Russian Muslims.

Two weeks after the commissariat establishment, elections to the Constituent Assembly were held on 26 through 28 November. Vast majority of Muslims voted for candidates from the Ganja list. During the elections to the Constituent Assembly the "Musavat" headed by Rasulzadhe and the Muslim National Committee led by Topchibashov and Khoyskii received 63% of votes of Caucasian Muslims. This great victory showed that national forces of the Caucasus had turned into a strong political organization. Consequently, the national bloc received 10 seats; a bloc of Muslim socialists - 2 seats; ittihadists - 1 seat. Bolsheviks received just 4,4% of votes, i.e. seat which vividly demonstrated that they lacked social base. The elections went to show that most Muslims from Baku, Ganja, Erevan, and Tiflis provinces were supportive of Azerbaijani political figures in their struggle for territorial autonomy. In December 1917, Ali Mardan bey resigned from his post of chairman of the Muslim Committee of South Caucasus, for he was elected to the Constituent Assembly. In the end of 1917, the Baku Committee acted as an inter-party organ. However, for heart disease Ali Mardan bey failed to take part in the work of the Committee and Seim. As is known, an idea of the Constituent Assembly belied, and on January 6, 1918, the government of Bolsheviks issues a decree on its dissolution. Expectations around the national question sank into oblivion. The disbandment of the Constituent Assembly became a crucial moment in separating national outskirts, including South Caucasus, from Russia. On January 22, 1918, all delegates to the Constituent Assembly from South Caucasus gathered in Tiflis. Two days debates ended with a decision to redouble seats at the Constituent Assembly and set up a regional legislative body - Transcaucasian Seim. On February 23, 1918, the 1st session of the Seim was held.

The first issue discussed in Seim after its creation was the start of peace talks with Turkey. The Trabzon discussions were the first time that Azerbaijani representatives to the Seim entered the diplomatic arena. On February 23, Vehib Pasha accepted the offer of the South Caucasian government to start peace talks. On the same day, a joint meeting of the South Caucasian Commissariat and the Seim was held. At the meeting, a letter from Vehib Pasha was read in which he stated that the Ottoman Empire was ready to start peace negotiations in Tiflis or Batum. Many Seim members were against holding the negotiations in those cities. Fatali Khan Khoyski, in his speech on behalf of Azerbaijani representatives, stated that the start of peace talks by the government would demonstrate its desire to be independent and stressed the importance of beginning without delay. In his opinion, the location of the conference was not important. Istanbul and Trabzon were suggested as suitable locations and, at the last moment, the decision was made to hold the talks in Trabzon...

The Trabzon conference and road to independence

On the eve of the Trabzon conference, the separate factions of the Seim discussed their responsibilities and defined their positions with regard to the peace. The Azerbaijani faction organized a meeting on this issue; the Muslim National Council had prepared an analysis of the events occurring within and around Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijanis were concerned with the concentration of Armenian forces in Baku after their return from the Caucasian borders; the danger to Baku as a result of the movement of British forces in the Middle East in the direction of northern Iran and the southern Caspian Sea; and the activity of Germans in the Caucasus and their intention to seize Baku oil. The Muslim faction considered it necessary to sign a peace agreement with Turkey without delay and stabilize the situation in the South Caucasus.

The delegation members who were supposed to go to Trabzon met on February 28, 1918. The Armenian representatives, invoking the right of nations to define their sovereignty, demanded autonomy for "Turkish Armenia" and expressed the idea that the Turkish government should withdraw its claims to Kars, Batum, and Ardahan. Ibrahim bey Heydarov, representing the Muslim Socialist bloc, considered this to be an intervention into Turkey"s internal affairs and stated that the South Caucasus nations could define their sovereignty only on the condition of doing so within the borders of Transcaucasia. In response to those who were blaming Turkey for breaking the Erzincan agreement, Mahammad Emin Rasulzade argued that the Turks likewise had a right to blame them for breaking the agreement. Two days before, Fatali khan Khoyski had spoken bluntly at the meeting of the Transcaucasian Seim, and there was a serious divergence of opinions between him and Evgeni Gegechkori.

A telegram from Lev Karakhan, the Russian Deputy Commissar of Foreign Affairs and Secretary for Soviet Russia at the Brest peace negotiations, which was received before the representatives of the Transcaucasian Seim set off for Trabzon, greatly complicated the situation.4 The telegram stated: "We decided to sign the agreement under discussion. The most difficult condition of the February 21 (March 3) agreement is the separation of Ardahan, Kars, and Batum from Russia in the name of sovereignty." One day later, Soviet Russia signed the Brest-Litovsk agreement and, in doing so, officially repudiated the decrees on "Turkish Armenia" signed by Lenin and Stalin two months previously. The agreement stipulated that Russia would do everything to evacuate southern Anatolia and return it to Turkey. Russian troops would be withdrawn from the Ardahan, Kars, and Batum provinces. Russia would not intervene in the formation of new state and judicial relations. With respect to Kars, Ardahan, and Batum, the border line that had existed before the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878 would be restored.

Despite the urgings of Turkey and their promises to provide assistance, the government of the South Caucasus had refused to participate in the peace negotiations and announce its independence and so was now in a bad position. After receiving a telegram from Lev Karakhan, the government of the South Caucasus, in telegrams sent to Petrograd, London, Washington, Rome, Tokyo, Istanbul, Berlin, Vienna, and Kiev, immediately expressed objection to the Bolsheviks" actions in the Brest-Litovsk negotiations. The telegrams stated that "The government of the South Caucasus considers invalid any agreement on Transcaucasia and its borders signed without its participation."11 But it was too late. Before the start of the Trabzon conference, Vehib Pasha demanded that the commander-in-chief of the Russian army in the Caucasus, General Lebedinsky, clear Ardahan, Kars, and Batum of Russian troops in accord with the Brest-Litovsk agreement.

The government and parliament of the South Caucasus were not declaring independence but, at the same time, did not want to side with the agreement signed by Soviet Russia. This contradiction was one of the most difficult problems that representatives of the South Caucasus faced at the Trabzon conference. The representatives of the South Caucasus arrived in Trabzon on March 8, and waited for the Turkish representatives on board the King Karl, on which they had traveled from Batum, until March 12. The conference officially opened on March 14. The head of Turkish delegation, Rauf Bey (Husayin Rauf Orbay), said at the beginning of the conference that the chairmanship would be given to heads of both delegations in turn. However, the representatives of the South Caucasus rejected this proposal. In his opening speech, Orbay stated that Turkey wanted to sign a long-term peace agreement with the South Caucasus on the basis of friendly relations.

The insistence of the South Caucasus representatives on their claims to Kars and Batum, their refusal to recognize the terms of the Brest agreement, and several other questions under dispute deepened the conflict between the sides. Turkey"s interest in negotiations was weakened by the Seim"s unwillingness to announce its independence. Akaki Chkhenkeli confessed, that, "Considering it objectively, Turkey is interested in the independence of the South Caucasus because the independence of the South Caucasus means the safety of Turkey"s northern borders." The leader of the Ottoman delegation, Rauf Bey, stated that representatives of Turkey were rejecting the declaration of the South Caucasian representatives because it interfered in Turkey"s internal affairs. In his opinion, the ideas expressed in the declaration did not comply with a friendly-neighbor policy. Official recognition of the South Caucasus government by Turkey was possible only if this government rejected its territorial claims on Kars, Batum, and Ardahan provinces on the basis of a special agreement. It would not contradict the obligations of Russia and Turkey, because Russia had accepted the right of its nations to sovereignty. The international agreement signed at Brest-Litovsk gave grounds for the Ottoman Empire to lay down a new order in these three regions; at the same time, the Ottoman government was ready to establish favorable economic relations between these regions and the regions of the Caucasus.

At that moment, Vehib Pasha ordered that the disputed territories of the South Caucasus be cleared. Intense discussions in the Seim on this issue showed that disagreement among the Trancaucasian nations was strong. While the Armenians and Georgians urged that the Turkish claims be rejected and war begun with Turkey, the Muslim faction proposed reaching an agreement with Turkey on the basis of mutual compromise. During the discussions, Mir Yagub Mehdiyev stated on behalf of the Muslim faction that it would not support the continuation of the negotiations if the independence of the South Caucasus was not announced. He noted that, normally, peace negotiations are held not by members of the Seim but by the minister of foreign affairs of a sovereign government. Discussion of territorial problems led to a situation in which the Georgians agreed to make concessions about Kars and Ardahan, on the condition of keeping Batum; the Armenians agreed to make concessions on Batum and Ajaria but did not want to give away Kars. The Azerbaijani faction stated that the government should fulfill its obligations according to the Brest-Litovsk agreement and give away Kars and Ardahan, because the majority of the population of these provinces was Turkish. They also thought that Ajaria should either become an independent Muslim republic as a part of the South Caucasus or, if this was impossible, should unite with Turkey. They also felt that Batum should stay within the South Caucasus, because the Black Sea port was an important outlet to other countries.

While discussions were being held in Trabzon and Tiflis, the Turkish army began to establish Turkey"s claims under the Brest agreement. Ardahan was captured on March 19, and Armenian troops were disarmed. The local population, which had been terrorized by the Armenian troops, supported Turkey in the military operations. Armenian representatives in the Seim and in the government, who had remained silent while Armenian troops used force against Turkish populations at every opportunity, now tried to blame the Musavat party for betrayal in connection with the attitude of the Muslim population.

The position on the issue of war and peace became clearer at the joint meeting of government members and leaders of the Seim on March 25. Hovhannes Kachaznuni, representing Armenia at the Trabzon negotiations, informed the participants that Turkey considered the declaration of the independence of the South Caucasus a necessity. It needed a state that would play the role of buffer between Turkey and Russia. Those speaking on behalf of the Azerbaijani faction clearly stated that they considered the declaration of independence of the South Caucasus inevitable and thus demanded it. In spite of the fact that Azerbaijani representatives participating in the discussions belonged to different political parties, none agreed to fight against Turkey. They stated that the Azerbaijani people would not fight against the Turks if war began. Khalil Khasmammadov said, If you do not fulfill Turkey"s demands, war is inevitable, and we cannot participate in a war against Turkey. If the Armenian and Georgian people feel they have enough power and strength, then let them take the responsibility on themselves and risk beginning a war with Turkey. No Muslim people will take part in this war.

Worrying news from Baku about bloodshed organized by the combined efforts of Armenian and Bolshevik forces worsened the situation of the Seim and the progress of peace negotiations. The Seim was informed about the events in Baku on April 2. Noe Ramishvili, a member of the Seim, evaluated these as the beginning of a Bolshevik attack on Tiflis and Bolshevik seizure of power in the South Caucasus. Shaken by the March bloodshed, the representatives of the Muslim faction demanded that immediate measures be taken against the Bolsheviks in Baku; otherwise, as they stated, the Muslim faction would boycott the Seim.

Positions on war and peace issues were being debated by factions of the Seim. Although after long negotiations on April 5, the representatives of the South Caucasus supported the idea of compromising over Kars and part of Ardahan, they refused to recognize the lawfulness of the Brest agreement. On April 6, the Turkish side, tired of repetition of the same solutions at the bargaining table, issued an ultimatum to the Transcaucasian representatives demanding that they provide an answer within forty-eight hours to the question of whether or not they accepted the Brest-Litovsk agreement. It was stipulated in the ultimatum that, if the South Caucasus wanted to reach an agreement with Turkey, it must proclaim its independence; only then could the diplomatic negotiations be continued.

On April 7, Akaki Chkhenkeli informed Tiflis about the ultimatum. Making reference to the anarchy in the country and the collapse of the front, he called for acceptance of the Brest agreement, except for the Batum part, and for an immediate proclamation of independence. At the same time, he wrote to Noe Jordania, the chairman of the Georgian National Council, "We are in a crisis situation, the level of the army is lower than critical, the Turks were allowed to get very close to Batum, the railroad near Chakvi will be cut off. If Batum is taken, we will have to think about the future of Georgia."

In Tiflis, events were moving in a somewhat different direction. As soon as the ultimatum about Batum was received, an extraordinary meeting of the Transcaucasian Seim was called. Evgeni Gegechkori, Irakli Tsereteli, Khachatur Karchikian, Yuli Semyonov, and others considered resistance to be very important and demanded in their statements that war be declared on Turkey. A call to war was echoed in the statements of the Armenian and Georgian representatives of the Seim.The antiwar views of the Azerbaijani parties did not succeed in changing the standpoint of the Seim, which on April 13 passed a resolution on war with Turkey. Martial law was proclaimed in the city. A military board with extraordinary powers was created, and an appeal was issued to all the peoples of the South Caucasus to protect their "fatherland" by taking up weapons. Irakli Tsereteli and others stated, in an obvious allusion to Azerbaijanis, that "as long as there is no betrayal from the rear," the Transcaucasian forces would be capable of resisting the Ottomans. Of course, there was no basis for such an assertion. Akaki Chkhenkeli, who was close to the front line and directly observed the situation there, could see very well that the Transcaucasian army was weak and falling apart and was not strong enough to resist an attack by Turkey.

The day after the war decree was accepted, Evgeni Gegechkori, in a secret telegram to Akaki Chkhenkeli, informed him that he must stop negotiations and leave Trabzon immediately. This news frustrated the Azerbaijani representatives in Trabzon. Mahammad Hasan Hajinski considered the decision of the Transcaucasian Seim as a violation of the peace and called it a "a scandal unequaled in the history of international relations" Angered by the situation, he stated that "he had a mandate from his party to go to Istanbul to take the final steps toward the conclusion of peace which is indispensable for us." Chkhenkeli, who was not in favor of war, did not fully terminate the negotiations but informed the Turkish representatives in a proper manner that the delegation must leave for Tiflis that same day in order to get instructions from the South Caucasus government. Chkhenkeli thought that upon his return to Tiflis, he would be able to distance the government from the war venture. He was concerned that war would intensify national conflicts in the South Caucasus. In his view, "war will endanger not only the independence of Transcaucasia, but also its unity." Chkhenkeli, who correctly evaluated the situation, "feared the war as much as he feared fire." Efforts by Chkhenkeli in the Georgian National Council to prevent the war did not bring about any results, as the capture of Batum by the Turks alarmed the Georgians and swayed them to support the war.

The war between the South Caucasus government and Turkey lasted for only eight days. On April 15, news of the capture of Batum was officially announced in Istanbul. After forty years, Turkey had regained Batum, with the assistance of the Ajarian population. The battle over Kars lasted longer. When the Turks had occupied most of the intended territories, and did not want to take any more losses, they put forward a peace proposal on April 22. In a telegram sent to Akaki Chkhenkeli, Vehib Pasha blamed the South Caucasus for the termination of negotiations and informed him that the issue of peace depended on the South Caucasus. The Seim accepted the offer to start peace talks. In fact, the South Caucasus government was relieved by this offer, as it turned out that waging a war was more difficult than declaring it. Serious dissatisfaction had arisen among the members of the Muslim faction because of the war and among the members of the Georgian faction because of the apparent defeat.

On April 20, there was an urgent joint meeting of representatives of all parties including the Azerbaijani faction of the Seim, with the exception of the Hummet party members. The Seim met that same day, April 20-that is, two days before receiving the offer to start talks with Turkey. All the leading parties, except for the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Constitutional Democrats, were in favor of accepting all the Turkish demands and declaring independence. Representatives who had stayed in Trabzon were not passive during this time. Soon after the negotiations were terminated, Enver Pasha had visited Trabzon and Batum and was received by the representatives in Trabzon. Mahammad Hasan Hajinski informed Enver Pasha that ending the hostility in Georgian-Turkish relations depended on resolution of the Batum problem. He made some attempts to retain Batum for the Georgians but without success. Noting that Turkey"s claim on Batum had been recognized by the Russian government, he stated that if the Georgians did not get carried away by Armenian politics and did not have a hostile attitude toward Turkey, Turkey would wish to see Georgia as an independent country and consider it a reliable neighbor. The Azerbaijani representatives wanted to sound out the views of Enver Pasha on such issues as the political structure of the South Caucasus and the future bilateral relations of the fraternal Azerbaijani Turks and Ottoman Turks. Enver Pasha said that Akhalsikh and Akhalkelek, which were Muslim districts, should join Turkey, as they had long wished to do. Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia could create a federation or a confederation with Turkey; they would continue having a common Seim and would exist in close union with Turkey. Enver Pasha also noted that, if it proved impossible to create a common Transcaucasian state, an independent Azerbaijan bordering Turkey could enter into a closer union with the Ottoman Empire, as close as the union of Austria and Hungary. He added that Turkey had already decided to take serious steps in the direction of providing aid to Azerbaijan. Hajinski relayed to the Muslim faction the news that Nuri Pasha,brother of Enver Pasha and Military Minister of the Ottoman Empire, would soon arrive in Azerbaijan, by way of Iran, with 300 military instructors, and that they were probably on the way from Tabriz to Araz at the time.

Finally, on April 22, as soon as the offer by Turkey was received, a historic meeting of the Seim was called, chaired by Nikolai Chkheidze. Three important issues were on the agenda of the meeting: (1) the independence of the South Caucasus; (2) the report by Akaki Chkhenkeli about the Trabzon negotiations; and (3) the formation of a government. After a long period of hesitation, late at night on April 22, 1918, the Seim proclaimed the Transcaucasian Independent Democratic Federative Republic by a majority vote. It was decided that a commission would be established that would prepare a constitution for the newly formed republic. The proclamation of independence was an important victory, primarily by the Azerbaijani faction and the Musavat party.

On April 23, the day after the meeting, Akaki Chkhenkeli informed Vehib Pasha that the Transcaucasian republic, which had proclaimed its independence, accepted all of Turkey"s claims and was ready to continue negotiations on the basis of the Brest agreement. He requested that the negotiations be continued in Batum. Chkhenkeli ordered an immediate ceasefire on the Batum and Kars fronts and that the cities should be cleared of troops immediately. On April 28, the newly formed Transcaucasian Independent Democratic Federal Republic was recognized by the Ottoman Empire. After that, there is only one month left before the declaration of independence of Azerbaijan...

Declaration independence of Azerbaijan

The last meeting of the South Caucasus Seim was held on May 26, 1918. In a speech, Irakli Tsereteli blamed the Azerbaijani faction for the dissolution of the Transcaucasian federation. He charged that the Azerbaijani faction as well as the Muslim population of the South Caucasus had refused to fight against Turkey, that it had sent its representatives to the Trabzon conference with no intention of negotiating, and that it had sent propagandists into the regions to persuade them to side with Turkey. Shafi bey Rustambeyov, who was responsible for answering Tsereteli, said that the arguments of the Georgian representatives who had decided to secede from the South Caucasus federation were false. In any case, if the Georgians did not want to cooperate, then Azerbaijan would not object to the dissolution of the Seim.

Giorgi Gvazava, a Georgian Nationalist Democrat, found a better way to resolve the disagreements. He said: "Gentlemen, let us stop arguing. Today we choose to dissolve the Seim, so let us do so in a friendly manner. We are meeting as friends, let us separate the same way." Thus, after Georgia"s statement about its secession, the Transcaucasian Seim decided to dissolve itself. The National Council of Georgia announced the independence of the Republic of Georgia on May 26 and formed a government cabinet with Noe Ramishvili as its head. The new government"s first political step in the international arena was the signing of an agreement with Germany that had been prepared beforehand. The Georgian government accepted Germany"s guardianship.

To discuss the crisis because of the dissolution of the Sejm, members of the Azerbaijani faction gathered on May 27 to hold an extraordinary meeting. In considering the complexity of the situation, the meeting decided to assume the responsibility for managing Azerbaijan and, hence, proclaimed itself the Azerbaijani National Interim Council. A vote by secret ballot elected Mahammad Emın Rasulzade a chairman of the Council. His candidature was backed by all Parties, except for "Ittihad". Hasan bey Aghayev and Mir Hidayat Seidov were elected his deputies, and Mustafa bey Mahmudov and Rahim bey Vekilov as secretaries of the National Council. Then delegates elected an executive body of the National Council composed of nine members in charge of various spheres of Republic"s life. Fatali khan Khoyskii was unanimously elected a chairman of the executive body.

The first meeting of the Azerbaijani National Council was held on May 28. Twenty-six people participated in the meeting, and three items were on the agenda: (1) information presented by Hasan Bey Aghayev about the latest events in Ganja; (2) reading of the letter and telegram of Mahammad Emin Rasulzade from Batum; and (3) the position of Azerbaijan related to the announcement of the independence of Georgia and dissolution of the Seim. Member of the National Council Khalil bey Khasmamedov made a report to substantiate the necessity of immediate declaration of the Azerbaijan Republic. He was backed by members of the National Council Nasib bey Usubbeyov, Akber agha Sheikhulislamov, Mir Hidayet Seidov, etc. The National Council (24 votes for, 2 abstained - Soltan Majid Ganizade and Javad Akhundov) passed a decision to immediate declare the state independence of Azerbaijan and proclaim "Act of Azerbaijan"s Independence". The declaration of independence consisted of six Articles:

1) as of today, Azerbaijan, which constitutes southeastern Transcaucasia, and has the right to national governance, is a genuine independent state;

2) the form of governance of the independent Azerbaijani state is established as a people"s republic;

3) the "Azerbaijan Republic" insists on building good relationships with all nations and states;

4) the "Azerbaijan Republic" guarantees citizenship and legal rights for all those who live within its territory, regardless of their nationality, religion, social position, beliefs, or gender;

5) the "Azerbaijan Republic" provides many opportunities for unrestricted development of all nations living within the territory of the republic; and

6) until the Constituent Assembly is formed, a provisional government consisting of the National Council and the Council of Nations, elected on territorial basis, will govern Azerbaijan.

Members of the National Council heard a text of the Act, then entrusted Khoyskii to form the Azerbaijani government. In an hour, meeting participants heard Khoyskii"s report on formation of the government. It stated, Fatali khan Khoyskii - Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers and concurrently Internal Minister; Khosrovpasha bey Sultanov - War Minister; Mahammmad Hasan Hajinskii - Foreign Minister; Nasib bey Usubbeyov - Minister of Finance and People"s Education; Khalil bey Khasmamedov - Minister of Justice; Mahammad Yusif Jafarov - Minister of Trade and Industry; Akber agha Sheikhulislamov - Minister of Agriculture and Labor; Khudadat bey Melikaslanov - Minister of Means of Communication; Post and Telegraph; State Controller - Jamo Hajinskii. The National Council of Azerbaijan carried out a great historical mission for the Azerbaijani nation by doing this. Whereas the majority of Muslim states were founded on a religious basis, the Azerbaijan Republic became the first Turkic state built on a universal basis. The founding of the Azerbaijani national state was a historic event in the destiny of the nation. Mammad Emin Rasulzade wrote, "The National Council of Azerbaijan, by publishing the Declaration dated May 28, 1918, confirmed the existence of the Azerbaijani nation in a political sense. Thus, the word "Azerbaijan" was understood not only in a geographical, linguistic, and ethnographic, but also in political sense."

On May 30, information about the establishment of the Azerbaijani Republic was telegraphed to Foreign Ministers of countries worldwide. A radiogram addressed to Constantinople, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, London, Rome, Washington, Sofia, Bucharest, Teheran, Madrid, Haague, Moscow, Stockholm, Kiev, Christiania, and Copenhagen, said, "As the Federative Transcaucasian Republic was disunited due to separation of Georgia, the National Council of Azerbaijan announced May 28 independence of Azerbaijan consisting of Eastern and Southern Transcaucasia. Your Excellency is kindly asked to inform Your Government about it. My government will temporarily by headquartered in Elizavetpol. Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Azerbaijani Republic Fathali khan Khoyskii".

At the Batum negotiations, begun by the Transcaucasian government and continued by the newly created republics, each put forward their articles of peace. It was necessary to define the borders of the newly created republics after the announcement of their independence. The Armenian republic was in the most complicated situation. Armenian representatives who applied to the Azerbaijani government for help before the signature of an agreement were met favorably. The chairman of the Ministerial Council of Azerbaijan, Fatali khan Khoyski, informed the National Council about negotiations with the Armenian National Council held on May 29. He stated that the Armenians needed a political center for the formation of an Armenian federation, because Alexandropol (Gumri) was still in Turkey"s hands. Only Erivan (Yerevan) could become such a political center; hence, it was prudent to give the city to Armenia. While addressing the meeting about this subject, Khalil bey Khasmammadov, Mahammad Yusif Jafarov, Akbar agha Sheykhulislamov, and Mahammad Maharramov evaluated the concession of Erivan to Armenia as an inevitable misfortune. The National Council agreed to give Erivan to the Armenians. Two days later, members of the National Council of Erivan-Mir Hidayet Seyidov, Baghir Rzayev, and Nariman Narimanov-rejected the concession, but the meeting of the National Council of Azerbaijan held on April 1 did not accept this rejection. Thus, the National Council decided to send a representative group consisting of Mir Hidayet Seyidov, Baghir Rzayev, and Mamad Yusif Jafarov to Erivan in order to resolve problems related to the conceding of Erivan to the Armenians. After this, the meeting discussed the Elizavetpol province issue. Nasib bey Usubbeyov andShafi bey Rustambeyov, who had returned from Ganja, presented information on this subject. At the meeting, it was decided to send Usubbeyov to Batum in order to inform the Azerbaijani representatives about the situation in the entire country. Negotiations between Azerbaijani and Armenian representatives in Batum on the subject of borders were held, and both sides reached an agreement. Azerbaijan would allow the creation of an Armenian state within the borders of "Alexandropol province" on the condition that Armenians abandon their claims to part of Elizavetpol province (Garabagh). In return, Azerbaijani representatives promised to help them secure signature of an agreement with Turkey.

Opinions within Turkish political circles about the creation of an Armenian state in the South Caucasus and about historically Azerbaijani territories being given to Armenians in order to let them create their own state were not unanimous. Prime Minister Talaat Pasha and Minister of War Enver Pasha, who were defining the foreign policy of Turkey at the end of World War I, did not favor the creation of an Armenian state in the South Caucasus. They considered that the creation would result in a weak country that would not be powerful enough to survive. Halil bey Menteshe ( the Minister of Justice) and Mehmet Vehib pasha (the commander-in-chief of the Caucasian Front), representatives of Turkey at the Batum negotiations, considered the concession of historically Azerbaijani territories to Armenians inevitable and, with that end in view, they advised the Azerbaijani representatives to recognize the existence of Armenia at the international level and to make certain compromises. When Halil bey, who was in Batum, informed Enver Pasha about the territorial compromises, he opposed these. In his telegram to Vehib Pasha, sent on May 27, he wrote, "As can be understood from the telegram of Halil bey, the Armenians, as a concession for those lands returned to us, want to obtain a part of the territories belonging to the Muslims of the South Caucasus, and Muslims would agree to this. I think that this is totally wrong. If today, a small Armenia, populated by five or six hundred thousand people and having sufficient territory, were to exist, then in the future this state would come to have a population of millions of people formed on the basis of American Armenians returning here. This will create a Bulgaria in the East, and this country would be a more harmful enemy for us than Russia. Enver Pasha preferred that the territories occupied by the Armenians, and in the first place Erivan province, where the majority of the population was Muslim, should be free of Armenians. He wrote, "If this situation, which is the most suitable for our benefit, does not take place, then it would be unavoidable to let the Armenians remain. In that case, it is necessary that they be allowed there in small numbers only. Only in that case could the well-being of our state and the present and future well-being of the Caucasian Muslims evade danger." In a reply to the telegram of Enver Pasha, Vehib Pasha wrote on May 29, 1918, "We cannot completely do away with the Armenians. In any case, we need to and have to let them exist." On the same day, Enver Pasha sent instructions to Batum, stating that the Ottoman government must have a direct border with the state that has Ganja as its capital. In his opinion, this border must pass north of Garakilse and through Nakhchivan.

It has to be kept in mind that "Treaty of Friendship between Imperial Ottoman Government and the Azerbaijani Republic" was signed on June 4 following the Batumi talks of May 11. On the part of Turkey, the Treaty was signed by Justice Minister Halil bey Menteshe and commander-in-chief of the Caucasian Front Mehmet Vehib pasha, on the part of Azerbaijan by Chairman of the National Council Rasulzade and Foreign Minister Hajinskii. That was the first treaty signed by the Azerbaijani Republic with a foreign state. An Article 4 of the treaty said that the Ottoman government undertook to render military aid to the government of Azerbaijan if required for order and security in the country.

Following the Batum conference, Turkey signed a treaty with Georgia and with Armenia on June 4 by recognizing their independence. Under the treaty with Georgia, Turkey had Kars, Batum and Ardahan, as well as Akhaltsikh and Akhalkalaki. Under the treaty with Turkey, Armenia had to recognize provisions of the Brest-Lithuanian treaty, following which Echmiadzin and Alexandropol passed over to Turkey, the latter had the right to operate a route Alexandropol-Julfa. A border of Armenia passed along Erivan, and the latter disposed of 6 km railway only. According to the Batum agreement, the Armenian republic was a state of the South Caucasus with a territory of 10,000 square kilometers. Hovhannes Kachaznuni, Alexander Khatisian, and Mikayel Papajanian signed the agreement from the Armenian side. According to the Batum agreement, the Georgian and Armenian republics were now obliged to guarantee safety and free development to the Muslim population living in their territories and to create conditions for the provision of education in native languages and for the free and unhindered observance of religious customs and ceremonies.

Following 3-week activity in Tiflis the Azerbaijani government and the National Council moved to Ganja on June 16. By this moment, first Turkish subdivisions headed by Nuri pasha came up to the city. On June 17, a crisis confrontation took place between supporters of Azerbaijan"s joining Turkey, Turkish command, and advocates of independence, however, it became possible to preserve Azerbaijan"s independence, and the same day a government headed by Khoyskii was formed. Portfolios in the new Cabinet were distributed as follows: Fatali khan Khoyskii - Prime Minister and Minister of Justice; Mahammad Hasan Hajinskii - Foreign Minister; Behbud bey Javanshir - Internal Minister; Khudadat bey Melikaslanov - Communication Minister; Abdulali bey Amirjanov - Finance Minister; Khosrovpasha bey Sultanov - Minister of Agriculture; Nasib bey Usubbeyov - Minister of People"s Education; Khudat bey Rafibeyli - Minister of Public Health. As soon as the governmental crisis was over, on June 23 on the whole territory of the Republic. Composed of the Turkish relulars and Azerbaijani volunteers, the Islamic Army aimed to liberate Baku as historical, political, economic, and cultural center from Bolshevik-Armenian aggressors and return the city to its true owners - Muslims.

Summer 1918: The Defeat of the Bolsheviks and the Crisis in Baku

The internal and external situation of Azerbaijan in the summer of 1918 made the liberation of Baku city an urgent matter. Toward the end of World War I, Baku had become an object of struggle between the Ottoman empire, Germany, England, and Soviet Russia. As the Russian White Guard General Anton Denikin phrased it, Baku"s oil plagued the minds and souls of European and Asian political leaders. While the Baku issue and the events occurring within the city should be approached from a domestic political standpoint, Baku was also a pawn in the world war. The military and diplomatic standoffs between Germany, Turkey, Soviet Russia, and England, and the confrontation between the Quadruple Alliance and the Entente states, propelled Baku into the fray. For all these reasons, the liberation of Baku was imperative. The march for Baku had started in the early spring. Both the Ottoman army led by Nuri Pasha and the British army wanted to reach Baku before the Germans reached it by way of Georgia.

The intrigues surrounding Baku have a place not only in the history of the war but also in world history. Peter Hopkirk, an officer in the British Intelligence Service working in the Middle East, wrote: "At the end of the last century Baku had been one of the wealthiest cities on earth. The discovery of vast oil fields in this remote corner of the Tsar"s empire had brought entrepreneurs and adventurers of every nationality rushing to the spot. Experts calculated that Baku had enough oil to heat and illuminate the entire world. So sodden was it with the stuff that

one had only to toss a match into the Caspian off Baku for the sea to catch fire for several minutes ... . For a few short years the town became a Klondike where huge fortunes were made and gambled away overnight. Baku"s new rich, some of them barely literate, built themselves palaces of great opulence on the seafront." At one point, Baku"s oil fields produced more oil than all of the United States.

When Azerbaijan declared its independence in May, the Baku Soviet of Worker"s Deputies and its executive body, the Baku Soviet of People"s Commissars, did not recognize the newly established national government and declared war against it by all available means-political, economic, military and diplomatic. The Bakinskii rabochii newspaper published articles denying the Azerbaijani people"s right to selfdetermination and wrote defamatory articles that spurred ethnic hatred toward the Azerbaijanis. In March 1918, ethnic violence directed against Azerbaijani Muslims in Shamakhi and other outlying districts was orchestrated by the Baku Soviet and Armenian militias. The organization of a so-called Armenian army heightened apprehension among the Muslim parliamentarians of the Transcaucasian Seim and reinforced their willingness to turn to Turkey for protection.

In their march toward Ganja, as well as through their unlawful activities, the Baku Soviet of People"s Commissars put further strain on an already fraught political situation in the South Caucasus. Almost all political and economic issues were settled by the barrel of the gun during the time the Baku Commune was in power. Before the newly established Azerbaijani government moved to Ganja, the Baku Soviet of People"s Commissars incited civil unrest and began preparations to attack Ganja. On June 2, Josef Stalin, while visiting the city of Tsaritsyn

(today: Volgograd), issued a command ordering the commissars headed by Stepan Shaumian to occupy Ganja. On June 5, Arsen Amirian, a former Dashnak who turned Bolshevik as a result of the revolution, evoked the Paris Commune slogan "Long live the civil war!" in his article "On the Lessons of History," published in Bakinskii rabochii. "Unfortunately," he wrote, "the mistakes made by the Paris Commune are once more repeated by our Baku Soviet ... . Instead of attacking the Versailles of the Caucasus and arresting all the leaders of counterrevolution, we give them an opportunity to gather, strengthen, and establish alliances with foreign enemies. This was a disastrous and an unforgivable mistake. But, "let us let bygones be bygones," as it seems that we are at an advantage. We do not need protection, we need to attack by all means, and I say again and again that we should attack. There is no other way out."

A day after this article was published, the Baku Commune"s Commissar of Military and Naval Affairs, Grigorii Korganov, ordered an attack on Ganja. The purpose of the attack was to destroy Ganja, the cradle of Azerbaijani independence. A telegram sent by Vladimir Lenin in mid-May played a role in the Commune"s aggression. Lenin wrote to Stepan Shaumian: "We are pleased with your resolute and decisive policy. Try to blend that policy with careful diplomacy, which is undoubtedly required by the difficult situation, and then we shall win ... . Thus far we are being saved only by contradictions, conflicts, and struggles among the imperialists. To be able to take advantage of these conflicts, we need to understand the art of diplomacy."

On June 12, Shaumian informed Lenin and Stalin by telegraph about the impending attack of Baku military units on Ganja. Simultaneously, massacres against Muslim populations in the regions began. In territories where war broke out, the Muslim population was subject to plundering by the Baku Soviet army, made up of 70 percent Armenians.7 Sometime later Shaumian, who took part in those military operations, acknowledged the atrocities committed against the local Turkic population by the command staff of the Baku Soviet of People"s Commissars - also made up mainly of Armenians. On May 22, the Soviet Russian representative Korganov wrote a report to the Soviet of People"s Commissars. He indicated that the Baku Commune"s army was 18,000 strong and most of the soldiers were Armenians, with only a few Muslims and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries. He stated in his report that "the Armenian peasants and the city democrats are willing to support a unitary Russian republic and Soviet power." On June 18, Korganov reported to the Baku Soviet of People"s Commissars that the situation at the front was favoring the side of the Bolsheviks and the "enemy" had taken numerous casualties. He said that, according to information provided by brigadier commander Hamazasp Srvandztyan, the "enemy" had launched an attack in Garamaryam village, where it was met with fierce resistance and retreated in a cowardly fashion. Hamazasp indicated that the casualties only numbered five dead and 49 wounded, while the "enemy" had about 400 casualties. This conclusion is further reinforced by the communiqué that was sent to the military-naval commissar of Soviet Russia, Lev Trotsky, by Boris Sheboldaev, who was at that time deputy-head of the Baku district. He wrote: "The armed forces of the Baku Commune, including officers, consist mostly of Armenians. On June 10, when the brigades and corps headquarters of the Commune army were established, it was evident that the corps commander (ex-colonel) S. Ghazarian, the chief of staff (ex-colonel of the headquarters) Z. Avetisian, and others were Dashnaks at heart. The command staff of the army was worthless and most of the Armenian officers were Dashnaks; this army will be loyal to Soviet rule as long as the "Russian influence" remains, but if the British gain the upper hand, it will be difficult to gauge what the response of the army would be. Considering that 60-70 per cent of the army is Armenian, surprises can be expected."

The overall command of the army was in the hands of colonels Avetisian and Ghazarian, both known anti-Muslim activists. There was also Hamazasp (Srvandztyan), who had fought as a guerrilla leader against the Turks and whom any Muslim was an enemy simply because he was Muslim. Accordingly, Armenian soldiers wantonly robbed, plundered, and committed acts of violence against the Muslim population on their way to Ganja and during attacks on Ganja. Ronald Grigor Suny noted that when the Red Army moved out from Baku toward Eizavetpol, they marched through the villages of Azerbaijani who were seldom friendly and were awaiting their Muslim brothers, the Turks. The Left Socialist-Revolutionary Grigory Petrov, who had been sent to Baku to help the Baku Bolsheviks, wrote of the barbarism he witnessed that was committed against the Muslims at Shamakhi, stating in his telegram to the Soviet Commissars of Baku: "I do not know whether I struggle for the sacred Soviet goal or I am among a gang of thieves." Petrov was in fact senior to Stepan Shaumian and he was sent to Baku as the Extraordinary Military Commissar for Caucasus Affairs, but it was said that he never put on airs and treated Shaumian as his equal.

By the end of June, the march of the Commune forces toward Ganja was halted at Goychay and four days of intensive fighting between June 27 and July 1 decided the fate at the front. The defeat of the Commune forces at Goychay saw many deserters from the Bolshevik army in the face of the ferocious actions of the Muslim army heading in the direction of Baku. Toward the end of July the Army of Islam reached the Baku suburbs and, in order to strengthen its numbers, Azerbaijani men born between 1894 and 1899 were drafted for military service on July 11. The draft significantly increased the number of Azerbaijanis in the Army of Islam; an influx of Russian supplies of weapons and other military supplies at the end of June did not have a great effect on the situation because of the Army of Islam"s greater numbers.

On July 20, the city of Shamakhi, which also was of strategic importance, was liberated on the way to Baku. This delay in the liberation of Baku by the Army of Islam increased the tension in the diplomatic struggle looming around Baku. In early July 1918 a report was prepared by the German Consulate to Constantinople (as Istanbul was still known in international diplomatic usage) which stated, "If we enter into negotiations with the Bolsheviks, then we could easily seize Baku, its oil fields and its reserves. However, if the Bolsheviks are forced to leave the city, they will set fire to the fields, and in this case neither we nor the Turks would be able to make use of the oil."17 This concern was also expressed by German Ambassador Bernstorff during a meeting with Mahammad Emin Rasulzade, in which he stated that if Baku was attacked by the Army of Islam, the Bolsheviks would destroy the city and set fire to the oil fields.18 It was reasonable to expect that the Bolsheviks could retaliate in this way, seeing that their actions from the beginning were based on a political gamble, as well as the fact that a directive to do this in the event of a defeat had been ordered by the Bolshevik central government. On June 23, 1918, Stepan Shaumian wrote to Vladimir Lenin, "If we cannot seize Baku, then we shall do as you instructed." Mahammad Emin Rasulzade, who was in Istanbul, wrote of his anxieties about the diplomatic struggle on the "Baku issue" to Azerbaijani Minister of Foreign Affairs Mahammad Hasan Hajinski: "The premise of the Germans is that if Baku is taken militarily, then the Bolsheviks will set fire to the oil fields and all oil reserves. Everyone understands that oil is as necessary as water to the Alliance at war. For that reason, the Germans want a peaceful diplomatic settlement to the Baku issue. We have learned through personal channels that there is a special agreement between the Germans and Bolsheviks about the oil. We would like to bring to your attention that the oil issue is more of a Turkish-German issue than it is an Azerbaijani-German issue. According to the Batum agreement the remaining oil belongs to Turkey. It seems that the Turks want to use the Germans in exchange for oil."

The Baku Soviet of People"s Commissars, after not receiving effective military support from Russia, hoped for the diplomatic support of Moscow and for the assistance of Lazar Bicherakhov, the leader of one of the Cossack military units in Iran, in case the situation worsened. The intervention of Soviet Russia, through the Germans, had delayed the Azerbaijani government"s entry into Baku. Recognizing its inability to prevent the Azerbaijani-Turkish attack, the Soviets wanted to hold on to Baku by diplomatic means, based on agreements made with Germany in 1918. As noted, the situation at the Western front and generally in the course of the war had significantly increased Germany"s interest in Baku. During the negotiations at a conference in June at Istanbul, Germany decided that it wanted Baku"s oil and would use Russia to get it, seeing that nothing had materialized from the joint efforts of Turkey and Azerbaijan. In Tiflis in June, the Germans had offered to dispatch a light military contingent to help Turkish-Azerbaijani military units to capture Baku, but "the Azerbaijani government was against this German proposal."

While German-Russian talks were underway in Berlin and Moscow, the situation in Baku changed from bad to worse. An item on the agenda was how to defend the city or whom should surrendor. In the end, they stopped at a candidature of tsarist colonel Lazar Bicherakhov, whose Cossack regiment was stationed in Iran. Earlier July the Bicherahov"s detachment moved from Enzeli towards Baku. Lazar Bicharakhov"s unit arrived in Alat on July 5 via the Caspian Sea. On July 7 he accepted the appointment as commander of the right flank of the Baku defense unit. Upon realizing that he was losing at the front, however, Bicherakhov did not fight; at the end of July, he withdrew his unit from the frontlines and retreated toward the west.

At the end of July, the situation in Baku worsened. The Baku Soviet"s record of violence against the Muslim population had the effect of isolating Baku from its outlying districts. In a mass meeting of non-Muslim workers held in Baku on July 24, the Socialist-Revolutionary, Menshevik, and Dashnak leaders approved and seconded a decision to invite the British to Baku in order to defend it from the attack of the Army of Islam. On July 25, an emergency meeting of the Baku Soviet was convened and Stepan Shaumian reported on the political and military situation in Baku. He rejected the proposal of inviting British troops and read the contents of a telegram received from the Soviet central government. The Azerbaijani government, meanwhile, made efforts to liberate Baku through peaceful dialogue and negotiations. On July 24, Minister of Foreign Affairs Hajinski wrote to Rasulzade that he had left for the Baku frontline in order to hold negotiations with the Bolsheviks about the surrender of the city. Hajinski continued: "The situation on the Baku frontlines is in our favor. Though it is a fact that our soldiers could not make much progress along the railway lines, they managed to move up to Karrar Station. However, we have been told that the Bolsheviks are in low spirits. The Baku newspapers we bought from Kurdamir and Salian dated July 18 wrote of disagreements between the Bolsheviks and other parties (at the same time among the right-wing Dashnaks, though I do not believe it). Actually, these disagreements have become a matter of nationality. Armenian Bolsheviks behave like barbarians in territories they themselves occupy and it is the Russians that are against those actions. There is talk at the Kurdamir front about 800 Russians who had laid down their arms and abandoned the front as a sign of protest against Armenian barbarism (they gathered Muslims in a mosque and burnt them, murdered women and children, committing indescribably heinous acts). They were arrested in Baku and now are incarcerated on Nargin Island. The Armenians have called for a general mobilization of troops. The Russians protested against it and do not want to fight. The Muslims are also in agreement on this matter. The Shamakhi-Baku route from Shamakhi to Ganja has been occupied by us. Armenian units are frenzied and are headed toward Baku, so fighting is expected on the outskirts of Baku."

On July 30, one of the leaders of the Commune"s army, Colonel Avetisian, informed the Baku Soviet that resistance was futile. On the same day the leaders of the Armenian National Council visited the Soviet of People"s Commissars and demanded the resignation of the Bolsheviks. Outvoted, on July 31, the commissars left Baku for Astrakhan on the ship Ardahan. On August 1, a newly formed government of the Tsentrokaspii was composed of officers of the Caspian fleet - Pechenkin, Tushkov, Bushev, Lemley, Ermakov; socialist revolutionaries Lev Umanskii and Abram Veluns; Mensheviks Qrigorii Aiolla, Mikhail Sadovskii; Dashnaks Alexander Arakelian and Sergei Melik Elchian. Like before, this government had not been related to Azerbaijan, and was a puppet regime composed of aliens. Formally, the power in the Tsentrokaspii was vested in officers and seamen of the Caspian navy but in fact, the real power was in the hands of the Armenian National Council, party "Dashnaktsutun" and other Armenian parties and organizations.

Like the previous government, the Central Caspian government did not include any Azerbaijanis and consisted wholly of foreigners. After its establishment, it addressed the Christian population of Baku, saying, "You are not alone in the struggle against the Turks. The Allied powers will help in the near future." Soon thereafter, the government decided to arrest the members of the Baku Soviet of People"s Commissars as well as Bolsheviks who were trying to escape from Baku. A conference was held following the repatriation and subsequent arrest of the commissars. The committees in the conference charged that the commissars not only abandoned their posts, they also abandoned the front at a time when it put the residents of Baku in the greatest peril. They also said that the commissars took food, military supplies, and weapons that were vital for the city"s defense. The conference charged the commissars with treason and deemed them the people"s enemies.

The maiden step of the Tsentrokaspii government was the invitation to the British in Enzeli to arrive in Baku. On August 4, the first British detachment headed by col. Claude Stokes arrived in Baku. A little later, another group of British, 1000-strong regiment, under the command of gen. However, the advent of Britishers did not improve the situation in the Baku front. From the first days of August, the Turkish-Azerbaijani army succeeded in narrowing the encirclement.

Between August 9 and 17, British military forces entered Baku with three battalions, one trench mortar battery and some tanks. As Hopkirk described the scene in Baku, "on August 17, 1918, the British disembarked in its sleepy port, only the ghosts of this once opulent past remained. In the aftermath of the war and the revolution, Baku must have looked much like Shanghai after the Communist takeover, though the decline of Baku had begun long before the arrival of the Bolsheviks." Harsh working conditions in the oil fields led to a number of strikes that had had an impact on the level of oil production. The industry was developing in a one-sided manner. Ethnic conflicts and the repression measures of the tsarist Russia dealt a heavy blow to the development of the oil industry. Oil industrialists considered it useless to invest in new technology. The war had isolated Baku from the world market and the city depended on its domestic market. All these factors led to the occupation of Baku by revolutionists. It allowed for the short-lived term of the Baku Soviet under the leadership of Stepan Shaumian and was soon thereafter replaced by the Central Caspian Dictatorship.

At a joint meeting between the British commander and the Central Caspian leaders on August 5, the British expressed their own dissatisfaction with the small number of troops in the Central Caspian army and how poorly trained they were. They said that it would be impossible to defend Baku with such a force. It was then that Menshevik Sadovsky asked the British officer sarcastically "And where is the great army you promised Abram Velunts and Ter-Agaian?" Dunsterville"s representative replied that England had never promised and never would promise that kind of a support to anyone, anywhere. It would be ridiculous to think that the British army could be moved there from Mesopotamia. Velunts observed that England valued its reputation highly, and that if the British came to Baku they would not leave the city so easily. To calm the Christian population of the city, the word was put out that another British contingent would arrive in Baku in the near future to fortify and equip the Central Caspian army. To raise the morale of the Central Caspian soldiers, a message from Lionel Dunsterville, who was still in Enzeli, was read. He said that on the basis of agreements with the Allied powers and at the request of the people of Baku, the British government was to send reinforcements and supplies to the besieged city. He said that in the struggle against the Turks and the Germans, the British army would ally themselves with the Central Caspian government and Lazar Bicherakhov. In closing, Dunsterville congratulated the "heroic defenders" of the city and said that if everyone were to fight against the enemy, then victory would come soon. On August 8, Captain Reginald Teague-Jones read Dunsterville"s declaration at a joint meeting of the Dictatorship and the British, in an attempt to inspire his partners. One unit of the small British contingent went to the front, mainly to oversee the technical installation of a communication system, while the rest stayed in the city to conduct military training.

Dunsterville"s assessment of the military forces of the Central Caspian Dictatorship was woeful. He wrote: "Supposedly manning the city"s defenses were 10,000, largely half-hearted, local volunteers. Of these, 3,000 were Russians and 7,000 Armenians. All had rifles, but few had received any proper military training. Most of them felt that they had already risked their lives enough, while some of them were even holding talks with the enemy. As for those Muslims remaining in Baku after the recent massacre, most if not all of them were ready to welcome the Turks and therefore presented a potentially dangerous fifth column, or enemy within." Anticipating the arrival of the Army of Islam, the Central Caspian Dictatorship, and in particular the Armenians, who occupied high posts in the Baku administration, held the populace hostage by various means.

After the arrival of the British, General Lazar Bicherakhov once more appeared on the political stage. He sent a telegram on August 3, in Russian and in Armenian, which was printed as a poster in bold capital letters and spread across the whole city. The telegram stated that the old government had had its hands tied in its struggle against the enemy. Now, Bicherakhov, together with Central Caspian forces and the British, had organized the army and was ready to take down the enemy. On that very day, August 2, the Army of Islam had liberated Bileceri Station, which complicated the picture, since Bicherakhov had said that he was the victor. Though this first "victory" was a deception, the British pinned their hopes on Bicherakhov. He was very famous among the Christian youth of Baku, such that they had taken to wearing the same hairstyle as he did. The British thought that if Bicherakhov returned to Baku, the city"s youth would be inspired to join the "heroic" army. In the tales spread about him in the city, Bicherakhov was called the "little Napoleon." In a telegram, Bicherakhov expressed that he was ready to take the place of the "defenders" of the city and wrote that "now all of Russia has pinned their hopes on the defenders of Baku." However, the Cossack attacks were short-lived. Despite the rhetoric in his telegram, Bicherakhov knew full well that he did not stand a chance against the Army of Islam, and without warning instructed his regiment to retreat by railway in the direction of Derbent. On August 8, he passed through Khachmaz and on August 12, he occupied Derbent and proceeded toward Petrovsk. Then, on August 15, Bicherakhov announced that he was moving south again in order to clear Derbent and Petrovsk of Bolsheviks, and then onward to provide support to Baku from Russia. He promised that he would return from the South Caucasus with 10,000 soldiers and sacks of grain. Bicherakhov concluded that the arrival of the British in Baku did not pose any threat to Russia. Though the Turks had surrounded the city, they could not occupy it. Meanwhile, at the front, about a thousand Cossacks, along with forces loyal to the Bolsheviks, made it impossible for the Central Caspian government to hold power.

On August 3, Mursal Pasha, the commander of Ottoman army at the Southern front, sent a letter to the head of the Armenian National Council of Baku, stating: "the Ottoman army is carrying out military operations to liberate Baku. If you surrender without a fight, the rights of all citizens regardless of race and religion will be guaranteed." He added that, should the Armenians wish to leave Baku for Armenia, no obstacle would be encountered. However, he warned, "if you show resistance, since there is no doubt that the city will be occupied, you will bear full responsibility for the bloodshed and damage that will ensue. In the event you are ready to surrender the city, send your representative with your response." The Armenian National Council and Central Caspian representatives, after the reading of the letter, decided not to respond to Mursal Pasha"s ultimatum, in the hope of getting support from the British and General Lazar Bicherkhanov. This silence meant the continuation of military operations.

In early August, the Army of Islam tightened the ring of blockades around Baku. On the 10th day of the month, villages in Absheron revolted against the Central Caspian Dictatorship and Mashtaga village was liberated by a regiment of the Army of Islam. On August 8, the August 3 ultimatum from Mursal Pasha was published in the Dictatorship"s newspaper. It gave hope to the small number of Turks who remained in the city after the bloody March events. The overthrow of Baku Bolsheviks in the summer of 1918 and the entry of the British temporarily alleviated the diplomatic pressure being applied by the Germans, which was previously taken quite seriously. Earlier in July, Mahammad Emin Rasulzade wrote to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Mahammad Hasan Hajinski, saying, "the Baku issue was settled for us in our favor. Undoubtedly, we should provide the Germans with some economic concessions. We asked the Minister of Foreign Affairs [of Turkey] whether we need to take reciprocal steps in relation to the Germans in this or some other way. He stated that there is no need at the present, and in case it is needed we will be informed. Enver Pasha asked me to inform you [M.H. Hajinski] that they sent fresh regiments in addition to the existing division and that Nuri Pasha said that the force is sufficient. In cases where urgent mobilization of the local forces is needed, the officer of the headquarters will be visiting there on Friday. According to the agreement concluded between the Germans and the Turks, Nuri Pasha was issued a directive related to the attack on Baku."

However, as German-Russian negotiations intensified, the diplomatic stance of Berlin toward Azerbaijan did not continue for long. In the middle of August, according to information sent to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from the Istanbul representative"s office, it became clear that the Germans were once more attempting to prevent the movement of the Turks toward Baku. Rasulzade wrote: "On the 17th day of the month, I visited Enver Pasha and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. I personally met with Talaat Pasha a day ago. The issue is that the Germans are not in favor of the movement of the Turkish army toward the Caucasus, and if truth on the matter be told, they want to halt the advance toward Baku. They fear that the Bolsheviks will destroy the bridges and burn the oil fields when they retreat, just as the British did when they left Romania. That is why the Germans prefer to settle the issue peacefully. Even some time ago, they supported the recognition of the independence of Baku with its outlying districts, including Shamakhi and Salian. The Turks protested against this declaration and, finally, according to both Enver and Talaat Pasha, they came to an agreement."